Bollywood Masala Mix

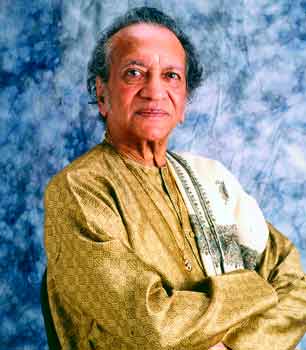

Sandhya Sen recalls fond memories of her many meetings with Ravi Shankar. The maestro turns 90

The east is east and the west is west, the twain can never meet, an idea that has been proved wrong, time and again, by the magic Pandit Ravi Shankar creates on the sitar.

When asked how he made the impossible possible, the sitar maestro replied, “Right from boyhood, I accompanied my elder brother Uday Shankar during his overseas tours. I was a dancer in his Hindoo Ballet troupe. Since then I am well acquainted with their taste, temperament, likes and dislikes. I felt that Western listeners were quite agreeable to the virtuosity, speed and varieties of music. Prior to our visit, classical musicians performed in the West but their style of demonstration failed to impress them because of their copybook approach. Actually, when playing before ‘alien’ audiences, one was required to prepare their mind for our type of music. It was just an experiment to get them attuned to our music. I explained before them that raga meant the melodious exposition of multifarious feelings of devotion, love, dedication, detachment, bravery, pathos, etc. They would attentively listen to the varied mood of raga music, concentrate on the chalan of melody and gradually get entwined with the temperament of Indian classical music.”

Looking back at half a century, it makes one wonder the degree to which Pandit Ravi Shankar has made Indian classical music popular abroad. The reason is not far to seek. He taught them the role of badi, sambadi, anubadi and bibadi notes and their role in the melodic structure of raga. He would play vilamvat to make them familiar with the temperament of slow tempo. The touch of his sensitive fingers on the resonance of meend in alap used to move them to tears. The rise in demand for sitar, sarod and tanpura forced Hiren and Hemenda to work round-the-clock to increase production figures.

How did Panditji succeed in making Indian classical music popular in the West, particularly in the USA? His answer is simple ~ through his devotion to music it is not a difficult task to propagate the beauty of our music. His motto is to convince the world of the dhrupadi mood of our music. Sometimes he would start with a fast tempo without deviating from sashtriyo norms to deal with the alap when listeners settled down to the raga tune. If one would start with the alap, their uninitiated ears wouldn’t have responded. They would simply skip the soiree.

What aspect of Indian classical music attracted them the most? “In those days of social unrest in Western countries, youngsters were in search of something new. Soon they lost their originality. As they were bewildered, they hankered for originality in music. I remember that our music originated from the Omkar sounds of sages worshipping on the banks of the Indus. You know my firmness in sticking to the purity of music. It is our real force of expression.”

Pandit Ravi Shankar was the first artiste to introduce solo recitals when artistes took part in music conferences. In 1956 Panditji appeared in a solo sitar recital at New Empire. The endeavour was not without struggle. The idea was new but the timing was not congenial. It overlapped with the glamorous Sadarang Music conference. Panditji was debarred from taking part in any function a week before and after the conference. The sitarist was at a loss since he was interested in participating in Sadarang. Initially he had to opt out of any one. But his cousin and secretary Jagadish Chatterjee convinced Sadarang’s secretary Kalidas Sanyal to exempt Pandit Ravi Shankar from the obligation because solo classical recital in public halls would usher (it was hoped) in a new concept for such programmes. Kalidas Sanyal relented and Panditji’s fiery and extensive repertoire opened a new door for artistes.

Pandit Ravi Shankar is also a great teacher. I remember one of his visits to the Ali Akbar College of Music. I was a student of the sitar. As we were playing, he suddenly pointed out to me, “Why are your fingers bending during meend, keep it straight.” Once corrected, it sounded different. Next he asked another student, “Why are you using the third finger within the small space of two or three purdahs? Don’t indulge in this habit.”

In the initial stages of popularising Indian classical music abroad, success was achieved through imitation. Back then I asked Uday Shankar whether it was true. He said: “If we try to simulate their style, they won’t listen because they know their music better than us.” I asked Panditji quoting his dada whether it was correct. He remarked: “Yes, it’s true. I’ve already said that my motto was to unite the East and West by fashioning a blend of harmony with our dhrupadi music. Once at a concert, after the raga music, I was playing dhun phase in a relaxed style. There was ragamala and folk tunes in the lighter vein and I simply added their favourite folk number Charlie My Darling. The response was overwhelming and I was convinced that only music and its melody can intensify a friendly relationship between two cultures.”

There was little scope for learning classical music from teachers a century ago. But now there are plenty of institutions in India but after Nikhil Banerjee no other artiste of that calibre is heard. “The reason is simple. Think of me and how we struggled. I came from a wealthy family. When dada sent me to Maihar to learn under Baba Allauddin Khan, he had doubts whether I would be able to withstand the strains of learning. I, however, was accepted as student. There was no fan, no electricity and I spent sleepless nights, bitten by mosquitoes... to me this was an unknown lifestyle. But I was always ready to bear the pain. Baba was a strict guru and he didn’t spare anyone. Whenever I thought of his angry face, it took little time to get attuned to his teachings. Believe me when I say that I forgot every other thing and played blissfully.”

“But now? Students approach the guru with tape recorders. Lessons are recorded on cassettes and are then practised. There is no dearth of talent but aspirants today hardly seek to reach a stage of high refinement. Some of them after learning run after publicity rather than focus on tutelage.”

Robuda is fussy about “correctness of music”. Once browsing through my review of his demonstration he advised me to write the correct names of ragas. Actually, the spellings of the ragas in vogue are different from the actual names. He told me, “You just come with the names of ragas and I’ll correct them. Writing good reviews is not the only task of a good critic. Bring the names to me at Mamo’s (Mamata Shankar) marriage, and I’ll correct them.” He actually did that.

A liberal to the hilt, Pandit Ravi Shankar appreciates every creation. When somebody told him about the worthlessness of film songs, he said: “Don’t look down upon film songs. Try to take rasa from all types of music. Leave pretensions aside and try to understand that film songs have sustained the varied trends of people’s music in our country. The singers are well versed in classical as well as folk songs. Old songs still impress me.”

The sitarist was well reflected in his memorable production Ghanashyam for which he was the script writer, music director and choreographer. Pandit Ravi Shankar is truly a diamond that sparkles no matter from which angle he is seen.

(Courtesy: The Statesman)

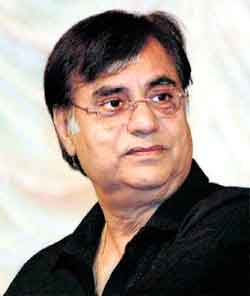

New Delhi, (IANS) — Ghazal maestro Jagjit Singh popularised the genre in films with songs like "Tum itna jo muskura rahe ho" and "Hoshwalon ko khabar kya". But the singer rues that the current lot of music directors lack a taste for such soulful renditions.

"Music composers in Bollywood today don't have a taste for ghazals and so the genre is missing in films. Composers are influenced by western music and are churning out more songs inspired by western beats," Singh, who is back with his new album "Inteha", told IANS over phone from Mumbai.

While Singh has enthralled music buffs with his lilting melodies in films, his strength has always been the non-film sector. Entering the music scene with "The Unforgettables", he carved a niche for himself through record sales of albums like "Beyond Time", "Sajda", "Insight", "Mirage" and "Soz".

His latest offering "Inteha", released by Big Music, encapsulates eight tracks and the singer says he came out with this one on the behest of his fans.

" 'Inteha' has a fresh flavour and a new treatment. The lyricists are new and so is the kind of music. The only thing old about the album is me. All my fans have been asking for 'new' ghazals since a long time. So I have come out with this album and I hope they like it," Singh explained.

While the music is composed by Singh himself, the lyrics have been penned by a team of young lyricists - Aalok Shrivastav, Payyam Sayeedi, Faragh Rushvi, Rajendranath Rahbar, Sanjay Masoom, Amjad Islam Amjad and Naseem Ajmer.

The singer, who enjoys a huge fan base in India and abroad, is leaving no stone unturned to promote the album.

While the launch took place on board a Kingfisher flight, Singh also featured on Zee TV's daily soap "Banoo Main Teri Dulhann" to promote it.

The singer, who will be performing in 16 cities in the US from next month, calls right promotion the "need of the hour".

"Today is the time of promotions. It is the need of the hour. If you don't promote your album or your music, nobody will know about it and the album will remain in stores," Singh said.

But what about claims that the market for non-film albums is shrinking and there are no takers for music in this category?

"The market is not shrinking. Proper promotion is required. Whatever is promoted well, sells. I don't think there is any change in the taste of audiences. People still like ghazals a lot," he asserted.

But the voice that evokes deep sentiments among listeners with his songs has a complaint.

"Today, channels are only playing Bollywood songs, so how will people come to know about an album that has been released? Even radio channels don't give airtime to ghazals that much," Singh rued.

He also feels there are budding Ghazal singers in the country but most of them start studying other genres in search of quick success.

"Most people want to become successful very soon. So even if they start as ghazal singers, they leave it and try singing some other form to gain instant recognition," he said.

Singh stressed that those who want to be a ghazal singer should learn Urdu along with classical music.

"Becoming a ghazal singer is not a joke," he said.