July 3, 2019 issue

Authors' & Writers' Corner

Kamil Ali

“We’ve lost her.” The doctor glanced at the heart and brainwave monitor. He switched off the machine to stop it’s flat-line alarm and detached the feeding needles from my veins. “I’ll leave you for a few minutes.” He hung the drip-tubes on the saline stand and left the room.

The priest joined my family at my bedside. He stood at the foot of the bed with a bible in one hand and a rosary in the other. My dad comforted my sobbing mom on my right while my two siblings dabbed at their eyes on my left.

When the doctor returned, I left him to examine my body and make notes on his report to confirm my death from meningitis. I followed my family out of the room to bask in the warm aura of light generated by their unconditional love.

I heard their thoughts and wordless conversations to me. I responded, but their earthly life-forms blocked two-way communication with the dead. I had the solutions to every problem and wanted to share the answers with them, but their mortal existence limited the reception of thought waves from beyond the living world.

During the two-day stay with my family after my demise, I followed each member as they prepared for the funeral. I could split myself and stay with each one whenever they went on their separate ways.

On the first night, I slipped out of my seven-year-old brother’s room when his eyes popped open, and he stared at me for a few seconds in the dark. With wide-eyed terror, he issued a blood-curdling scream. My parents and my twin sister bolted into the room.

When he told them that he had seen me, they tried to convince him that I had gone to heaven to become one of God’s angels who would protect him, not harm him. Their nervous glances around betrayed their own fears of potential ghostly encounters.

Our parents allowed him to sleep between them for the rest of the night. My thirteen-year-old twin sister joined him for a family sleep on the king size bed. Each one sensed my presence, but the safety in numbers comforted them. My spirit seemed to use up the energy around me, which dropped the temperature a few degrees. Body heat generated from their huddle under the thick bedcover gave them comfort.

My presence among family members during daylight hours had a positive effect, which reversed at night. On the second night, I stayed out of sight from the fading light of dusk until the sunrise at dawn. Around midnight, my mom got out of bed and sat on the living room sofa. She stared at the wall and relived visions of our twin births and antics as toddlers. Tearful smiles lit her face. My dad joined her a few minutes later, and they whispered fond memories to each other. My twin sister and younger brother turned the sofa into a family assembly location. They fell asleep one at a time.

I saw my body once again on the day of the funeral. The funeral home had dressed me in the princess outfit my mom had bought for the occasion. My sister wore the same outfit, hairstyle, and makeup. My angelic appearance and sleep-in-peace smile warmed every heart and moistened every eye.

Relatives and friends came from far and wide. Students and teachers stood in a crowd that stretched from the viewing room to the street. The death of a thirteen-year-old evoked sympathy from the community. Everyone offered support to my bereaved family. I heard every distinct thought about me, even though they bombarded me all at once.

Heartbreaking eulogies rendered by my parents and siblings, infused an atmosphere of empathic sorrow and pain for the loss of one so young.

Sniffles accompanied the lowering of the casket by the cemetery staff into the rectangular hole in the ground. I saw my body through the casket cover. A glance around at the other cemetery plots revealed bodies in various stages of decomposition. Some had completely blended in to become a part of the natural elements.

The crowd of mourners left to attend a reception at the church to celebrate my life. My ability to will myself to any location at the speed of thought gave me the advantage to arrive before everyone else.

My family thanked everyone for their support and sought acceptance of the fact that I had left their physical presence forever. Once they gained closure, a shaft of light appeared above. It’s welcoming radiation hugged me and glided me upward to a blinding glare at its other end.

In the presence of an omnipotent energy, overwhelming compassion filled me with awe. Euphoria replaced every other emotion. Unparalleled joy welcomed me into a new world of everlasting peace and serenity.

After the welcome into paradise, a soft aural hue replaced the bright light. Souls floated as orbs, free to move in any direction they wished. I connected with my deceased ancestors and joined them to explore the richness of a never-ending journey through bliss.

Without a body that requires nourishment, the soul experiences complete contentment with no materialistic needs. Universal awareness eliminates the need to seek knowledge.

My family and friends communicate with me through dreams that assure me of my continued existence in their memories. I have a window into their world and provide guidance through subtle signs that I place before them.

My body has become one with the Earth. My soul soars.

in Guyana

By Romeo Kaseram

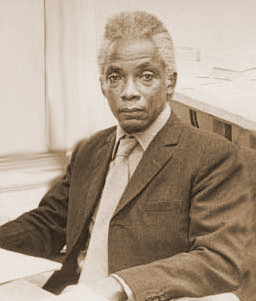

Denis Joseph Ivan Williams was born on February 1, 1923, in Georgetown, Guyana, to Joseph Williams, a merchant, and mother Isabel (neé Adonis). He received his early education in Georgetown, graduating with a Cambridge Junior School Certificate in 1940, and the Cambridge Senior School Certificate in 1941. Victor Ramraj, writing in Fifty Caribbean Authors, tells us Williams had two early calls to the arts, one being the desire to be a writer; however, the pull was stronger to become a painter.

It was Williams’ emergent promise as a painter that won him a two-year British Council Scholarship in 1946 to attend the Camberwell School of Art in London, where he studied until 1948. He continued to live in London until 1956, where he lectured at the Central School of Fine Arts and taught at the Slade School of Fine Arts. Williams also held several one-man shows, exhibiting his work at the Gimpels Fils Gallery. In this time, he crossed paths with the emerging, and now eminent Caribbean novelist, George Lamming. As Wikipedia notes, Williams produced the artwork for Lamming’s first novel, the well-known bildungsroman, In the Castle of My Skin.

In the decade from 1957 to 1967, Williams continued his teaching career, traveling to the Sudan, where he lectured in art and art history at the School of Fine Art in Khartoum. He also taught at the University of Ife, and the University of Lagos in Nigeria, and at Makerere University in Uganda. In ‘Notes on a Life: Denis Williams 1923-1998”, published in the Journal of Contemporary African Art, Carl E. Hazelwood tells us Williams taught and conducted research at both the University of Ife and the University of Lagos in Nigeria, and founded museum collections of African art and artifacts at both institutions. Additionally, Williams also participated in the workshops that engendered the Oshogbo contemporary art movement in Nigeria, and in so doing, “configured a new image and a new life for himself”. Wikipedia notes Williams also published numerous articles on the history and iconography of West African classical art, expressed especially in brass, bronze, and iron. In 1974, he published the controversial book, Icon and Image: A Study of Sacred and Secular Forms of African Classical Art.

In 1968 Williams returned to Guyana and established a homestead in the Mazaruni District. The move into the hinterland, Ramraj writes in the Guyana Chronicle in 2014, was due to a growing discomfort with Europe and Africa. Ramraj tells us Williams decided “in the 1960s to return to his own ‘primordial world’ in the interior of Guyana”. He adds: “[Williams] lived from 1968 to 1974 in the Mazaruni area of the Guyana hinterland, writing and painting and researching Amerindian tribal art, particularly their petroglyphs. He describes this as a ‘tremendous’ period of his life, one free of ‘twentieth-century anxieties’. He recalls with pride the building his own home, acting as midwife when his wife gave birth, and having no library, no books other than – oddly – a regular subscription to The New Statesman, through which he ‘kept up with language’.”

The exposure to archaeology in Sudan renewed Williams’ interest in the discipline, which he applied to his Guyanese homeland. As Wikipedia notes, Williams wrote to the Smithsonian Institution in 1973, saying, “[My] interest in these antiquities is that they may explain something about the who and how, as well as the when of the arts of the Guyana Indians.”

In 1974, Williams was appointed as the director of the newly created Walter Roth Museum of Anthropology in Georgetown, the role creating the opening for his archaeological explorations. Wikipedia notes Williams first concentrated on petroglyphs, recording its designs, performing excavations to recover the tools used, and observing the environmental contexts. The effort contributed to Williams’ Master of Arts thesis, entitled The Aishalton Petroglyph Complex in the Prehistory of the Rupununi Savannas, which he submitted to the University of Guyana in 1979. He later elaborated on its ideas in an article in 1985, which was published in the journal, Advances in World Archaeology. In 1978 he founded Archaeology and Anthropology, the journal of the Walter Roth Museum of Anthropology, and with his assistant, Jennifer Wishart, in 1986 initiated a programme for junior archaeologists in Guyanese secondary schools.

Williams authored two novels, Other Leopards (1963), and The Third Temptation (1968). He also produced several works on West Indian and African art and anthropology: Image and Idea in the Arts of Guyana (1970); Contemporary Art in Guyana (1976); Guyana, Colonial Art to Revolutionary Art, 1966-1976; Ancient Guyana (1985); Pages in Guyanese Prehistory (1995); and the posthumous Prehistoric Guiana (2003). Along with Archaeology and Anthropology, he also edited the journals Odu (University of Ife Journal of African studies), and Lagos Notes and Records.

Williams received numerous prizes and awards. In 1976, he won the first prize in the Guyana National Theatre Mural Competition. He received numerous research grants from institutions as the International African Institute, London; the University of Ife; and the Smithsonian Institution for work in archaeology and anthropology. In 1973, he received the Golden Arrow of Achievement Award from the government of Guyana, and in 1989 the Cacique Crown of Honour.

Also, in 1989, he was awarded a DLitt (honoris causa) by the University of the West Indies. In 1994, he was presented with a Certificate of Recognition, the Gabriel Mistral award for culture, by the Organisation of American States, and in 1998 he was honoured with the ‘Cowrie Circle’ by the Commonwealth Association of Museums.

Writing in the Guyana Times International, Petamber Persaud tells us Williams “lived on three continents at crucial times – times of intellectual upsurge, times of political ferment and times of creativity in the arts”. He adds: “Williams was caught up in the action wherever he went, sharpening his perception of the living and the past as reflected in the innovations found in his art, craft and writing.” At his death in Georgetown, Williams was conducting archeological research into the pre-Columbian history of Guyana. He died on June 28, 1998, shortly after a cancer diagnosis.

(Sources for this exploration: Fifty Caribbean Authors, Peepal Tree Press, Guyana Times International, Guyana Chronicle, Journal of Contemporary African Art, and Wikipedia.)