January 23, 2019 issue

Authors' & Writers' Corner

ancestry research

There have been many useful uses for scientific DNA testing. It has been used in crime investigation, in medical diagnosis and treatment and historical research. It can infer intelligence and other traits. But some caution needs to be utilized.

The growing interest of “moderns” in their ancestral past is understandable, seeing that many older folks rarely discussed their past. The good, the bad and the ugly were often hidden from their children. Skeletons remained in closets where many believed they belonged. Conservative governments are taking increasing interest in the ethnicity and origins of their citizens, not usually a healthy development. Race, ethnic origins, and immigration are becoming part of national debates. Technology is opening up new avenues to investigate and disclose. DNA ancestry investigation is one of those areas. It is a relatively new science or some say “pseudo” science. The validity and reliability of test results can be questionable. The scientific method is not strictly followed or explained.

A number of folks who have sent their DNA to different companies have got different results! Surprising? Not at all. To clarify the issue, the population into which your DNA is thrown may be around 10 million. This is a very small fraction of the world population which are billions, numerically speaking.

Furthermore. because of the costs of the test, it is a select group who can afford it, usually in highly developed countries like the United States. The vast domain of poor folks in many poor parts of the world, is excluded. The group or sample is biased as many of our relatives who live in poor countries would thus be excluded as many regions are not represented.

The subjects used to compare DNA are live people. Although it is reported that you can get DNA from the deceased in certain circumstances, how far back you can go is questionable. So to suggest that you have direct connections to royalty and other notable folks who lived hundreds of years ago is more than far fetched. It is however great for the ego and for discussion at the water fountain at work. DNA testing companies play on this in describing results.

Different companies use different samples, generally speaking, and not necessarily the same testing analysis instruments. Are you then surprised that results can be different? There are also questions about the privacy of results. It is possible that DNA reports can be hacked – just about anything can be hacked these days. Police and government can perhaps have access to test results in some circumstances such as in the “national interest”. Employers can make demands for results for certain jobs. It may be utilized for ”ethnic” cleansing; for citizenship; for marriages; and inheritance. You may be picked out and used as a guinea pig for an experiment, not necessarily ethical.

Who owns your DNA? What happens if you find out you are related to Jack the Ripper, the infamous London murderer or even to the notorious Trump? Can you face the results?

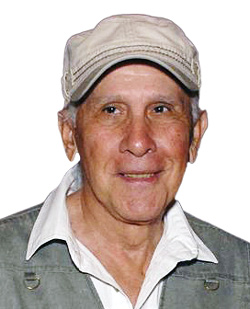

If you are interested in discovering your ancestry, I would suggest an alternative approach. I have been conducting a genealogy research or family tree for over 25 years, using traditional methods. The task is in fact never-ending. Most folks want a “quickie” test – a quick and easy test. That is definitely a selling factor in DNA ancestry testing.

Using the traditional approach, you can get specific information about births, deaths, marriages, offspring (legitimate and illegitimate), locations, religions, church records, occupations, illnesses and more.

Historical research has a reputable history in the arts and sciences. The first thing your doctor asks for is your past medical history. Libraries, censuses, immigration, interviews, books, documents, tapes and photographs can provide interesting and vital clues. You need to be like a detective, following every clue.

This journey has carried me to travels on three continents over decades, roaming through graveyards in foreign countries, facing foreign languages, beating the bush and spending a tidy sum of money in the process. It is hardly a quest that can be accomplished by sitting at your desk at a computer or spitting into a tube.

I was fortunate through my training as a researcher to learn some of the tools of the trade. It is not easy to question people who don’t want to talk or to jog their memory of the past. Sometimes it is like getting ”blood from a stone”. They often ask “Why are you doing this?” “Leave the dead alone”. ”Let them rest in peace”.

A useful and necessary strategy is to try to cross-validate data. This is true of scientific and other investigations, in detective work and legal cases. You have to ask the right questions to get the right answers. You have to ask yourself, why you are doing this. For me, I have always had an interest in history and a number of my books and articles point to that. Our children show a passing interest and find other ways to occupy themselves. Perhaps later, when my wife and I are dead, they may show more interest. There may be a castle, an estate, a title, a kingdom somewhere that I can inherit (smile). Most folks, I guess, just want to connect with others.

In the long run, the science of DNA ancestry should improve and the results become more valid and reliable. The more respondents, the bigger and more representative the pool will help. Investigation by traditional methods does not necessarily exclude using DNA. The two methods may complement each other. As it stands now, DNA ancestry testing raises more questions than answers. If the creeks don’t rise and the sun still shines I’ll be talking to you.

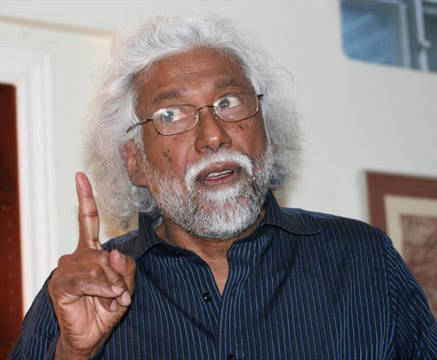

Ian McDonald and Peter Jailall, People of Guyana, Middle Road Publishers, Toronto, Ontario, 2018, pp.91.

A review by Frank Birbalsingh

People of Guyana combines new as well as previously published poems by Ian McDonald and Peter Jailall, two of Guyana’s best-known poetic voices, into one volume. This original literary venture is not merely an anthology of works by two authors, but an original, indeed a unique literary enterprise in which each author interweaves his own poems so intricately with those of his fellow poet that together their poems become essential components of one authentic literary work. McDonald who lives partly in Guyana and partly in Canada, is also a novelist, dramatist and non-fiction writer, while Jailall, a retired school teacher, is well known for public readings from his work in Toronto where he has lived for most of his life. Of the forty-six poems in People of Guyana, twenty-five are by McDonald and twenty-one by Jailall.

Poems in People consider subjects that are exclusively, quintessentially Guyanese; but whether they deal with local Guyanese people, places, scenes and events, or biographical sketches of individuals, they are in no way artistically limited by their national, regional or geographical connection. Local situations, people or events may be one thing, but themes illuminating people’s reactions and feelings are quite another matter.

Nothing confirms the artistic success of poems by McDonald and Jailall more than the intensity and sense of grandeur they elicit in plumbing themes of thought and feelings experienced not only by Guyanese but by people everywhere. A typical example is McDonald’s “Betty” which describes an old, probably Indian-Guyanese woman “in a run-down logie room” where her life “was as nothing to her,” and “all women’s’ lives were as nothing,” whereas “boys were princes” and her husband abandoned her for another woman. Betty’s adverse experience, both as a woman and labourer, proclaims universal feminist and humanist themes of interest to people everywhere.

Defiance, persistence, endurance and indomitable will against oppression are also seen in two of McDonald’s poems about Amerindians, the first people of Guyana. “Amerindian,” the first poem in People, is about an Amerindian whose plight is that he migrated to a town where he died, presumably from cultural alienation since, as the persona comments: “He [the Amerindian] should have died with jaguars and stars.” The persona appears aggrieved by the Amerindian’s tragic sense of cultural displacement when he further claims: “When buildings in this upstart town / Again are lost in sea-drowned grass/ The forest will stay.” In “The Last of her Race,” Miaha, an Amerindian woman, who is “Frail, desolate decayed,” and “old and toothless,” also feels this unbroken sense of connection to her ancestral forest.

Although most poems in People are short lyrics, “Village People” by Jailall and “Death of An Old Woman” by McDonald are each four pages long, and offer more extended treatment of their themes. In “Village People,” for example, in August 1996, Jailall’s persona re-visits Ann’s Grove, a largely African-Guyanese village where the poet lived three decades earlier, before migrating to Canada. Not surprisingly, ethnicity and immigration are main themes, and the poem is awash with good natured reminiscence as the persona greets a former neighbour, Coolie Gyal, who reminds him: “We lived so lovingly in the village/ Eating from the same plate.” But such fond nostalgia masks darker currents of “racial nonsense,” or deadly ethnic conflict between Indian- and African-Guyanese recalled by Mr. David, a returning African-Guyanese migrant who also formerly lived in Ann’s Grove.

“Death of an old Woman” another McDonald poem offers an equally sombre reflection on the cremation of an eighty-five-year old Hindu woman with “heaped aromatic wood around her like a house,” and flames: “tall and climbing clear” until her ashes are cast upon “the sacred bosom of the sea.” Even more impressive are a series of magnificent epigrams strategically deployed, throughout the poem to shed light on the irresistible but challenging ambiguity of the intriguing mystery of life and death: “Entirely I am burned away/ I die and then I cease to die,” or: “Life lasts a moment,/ yet it does not end” or yet again: “Though darkness seems the lot of man, / all the universe is radiant light.” Such wondrously probing and percipient, epigrammatic insight is seen again in McDonald’s poem about a woman nick-named Mother Tango: “She [Mother Tango] can sideways drag herself to Heaven / Faster than you or I can ever walk or run.”

It is no accident that reflection by both poets in People should be so unflinchingly, yet soberly tragic. In “For Mervyn” Jailall’s report on the apparently random shooting of: “a poor/ coolie boy” and his father from the countryside is horrendous enough; but it does not remotely match the depth of inner turbulence that Guyanese feel about their colonial history as we see in “Estate Talk” where a returning female immigrant hears about the drunken irresponsibility of the husband of another woman from the plantation where the persona formerly lived: “Da man da / Na kay if / Good Friday faal / Pan a Sateday.” [That man there / Doesn’t care if/ Good Friday falls / On a Saturday.]” For their brevity and simplicity, grandeur of psychological insight and philosophical depth emanating from such controlled despair, these lines are positively Shakespearian.