April 3, 2019 issue

Authors' & Writers' Corner

Kamil Ali

After Billy left for work, Darlene hand-washed the breakfast dishes while three-year-old Natalie played with her toys on the kitchen floor. The toddler spoke to her dolls like a parent and responded on their behalf like her children.

“Samantha, stop hiding from me.” Natalie made up a name for each of her four dolls. “You’re scaring me.”

Darlene spun around in time to catch Natalie scurrying out of the kitchen after Samantha.

When Billy arrived home, Natalie abandoned all her toys to enjoy her dad’s attention. He devoted his entire evening to his family with playtime for Natalie and funny work stories for Darlene. After supper, they watched some TV until Natalie fell asleep in his arms. They put her to bed and set up the camera in a hidden location to get a full view of the baby’s room. Billy set the camera’s monitor on the night table on his side of the bed.

Static noise from the fuzzy monitor awoke Darlene in the middle of the night. She shook Billy awake and pointed to the screen. He picked up the monitor and fiddled with the controls, but no defined image appeared. Billy sprang off the bed with the monitor in his hand and hurried to the nursery with Darlene at his heels. The nightlight in the baby’s room illuminated an angelic slumbering Natalie. The monitor’s screen cleared and displayed the same picture of normalcy until Darlene tapped Billy’s shoulder and pointed to the dolls on the night table. Samantha had gone missing! Darlene followed Billy around the room in search of Samantha without success.

Darlene spun around and glanced in the direction of a child’s muffled giggles outside the nursery. Goosebumps covered her body. Billy dashed out of the bedroom to investigate. Darlene grabbed the sleeping Natalie and followed her husband to the kitchen. A movement at the side of her eyes startled her. She tugged at Billy’s sleep-shirt and pointed in the direction of the phenomenon. The monitor’s screen fizzed with static. Billy led his family back to the bedroom. Samantha had returned to her place with the other dolls. The monitor returned to normal. A sick feeling churned Darlene’s stomach. Had they just witnessed a supernatural event? All three family members had experienced Samantha’s unnatural behavior. Billy closed the door to the nursery to trap the dolls in the room.

“Billy, these bedroom doors don’t have locks.” Darlene shivered from a chill. “I don’t want to stay in this house tonight.” She shook his arm. “I’m scared, Billy.”

“We have to get to the bottom of this.” Billy reasoned with his wife. “Maybe someone is playing a prank on us.” He made a casual reference to his friends, who always tried to trick each other with practical jokes.

“This is no joke, Billy.” Darlene held back tears of frustration. “We’re in danger, can’t you see.” Anger at her husband’s stubborn defiance made her shout.

“Trust me, honey.” Billy put an arm around her shoulders and led her to their bedroom. “I’ll protect you and Natalie with my life.” They entered the bedroom, and he closed the door behind them. “My mind is too logical to accept supernatural stuff.”

Darlene believed in her husband. She placed Natalie between them on the bed and hugged her. Billy lay on his back with the monitor on his chest to keep an eye on the nursery.

“Oh my God!” Darlene’s scream jerked Billy out of sleep. She had lain awake and had stared at the monitor until it crackled then cleared. “Samantha is missing.” The bedroom door opened a crack. Darlene shrieked when the doll’s eye came into view before terror paralyzed her vocal cord. She snatched Natalie and jumped back to distance herself from the doll. Billy followed her line of vision and yelled at the doll to leave his family alone. He threw the monitor at the doll. The door slammed shut, and the monitor exploded into a hundred pieces.

“Let’s play hide and seek.” A child’s giggles echoed throughout the house. “Catch me if you can.”

The family scrambled out of the house and drove to Darlene’s parents a few blocks away. They sold the house without finding out what caused the paranormal activities that night. They had no desire to find out and preferred to leave it behind them like a bad dream they wanted to forget.

Trinidad voice

By Romeo Kaseram

By Romeo Kaseram

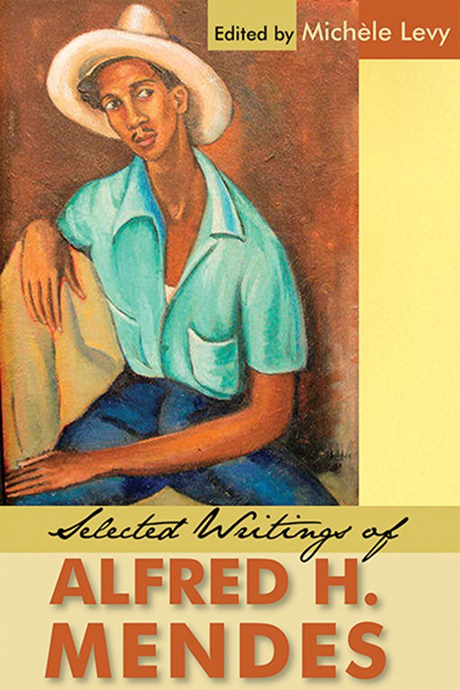

Alfred Hubert Mendes was born in Port-of-Spain, Trinidad on November 18, 1897, the eldest of six siblings of four brothers and a sister. Michèle Levy, in her ‘Introduction’ to The Man Who Ran Away and Other Stories in Trinidad in the 1920s and 1930s, tells us Mendes was third-generation Portuguese Creole, the family was not well-off, and lived in a working-class area of Belmont just outside Port-of-Spain. However, Mendes’ merchant father later became a highly-successful businessman. With a financially improved status, the family moved into a middle-class neighbourhood, and settled in a large house in the capital city.

In Fifty Caribbean Writers, Reinhard Sander notes with the family “well-to-do”, Mendes’ father “in keeping with this status” sent his eldest son to England in 1905. While there, Mendes received a secondary education at Hitchin Grammar School. He returned to Trinidad in 1915 following paternal intervention to ensure his son’s safety during the Great War of 1914-18. However, as Levy points out, the defiant young man enlisted with the Merchants and Planters Contingents of Trinidad, and headed for “the arena of battle in Flanders, where he saw action as a rifleman” in the First Rifle Brigade, returning home in 1919. Sander’s notes although Mendes was decorated for bravery, “he was appalled by the sordidness of the struggle and began to see the war as a mindless sacrifice of life, engineered by the major European powers in their pursuit of selfish imperialist aims”.

In contrast, Sanders tells us the 1917 October Revolution in Russia presented Mendes with a new framework to interpret modern society. Quoted in Kenneth Ramchand’s 1977 text, Mendes commented: “Today, after this long distance from the Russian Revolution, no member of the two generations that followed it can have the faintest idea of how moved, how uplifted and how hopeful those of us were who could sense its implications and its inherent possibilities. World War I with its ghastly disillusionment and its Death, its broken promises and its cynicism had left us eager to clutch at any straw of hope in the drowning sea.”

Levy notes Mendes’ writerly urge started as a schoolboy, in the realisation “what he most wanted to do in life was to write”. She adds: “This urge crystallised after his return to Trinidad in 1919 from the war in Europe, into the desire to write about his island home from the perspective of a native…” Accordingly, the young Mendes “threw himself into the cultural life of the colony: joining literary and debating societies; attending performances by local amateur dramatic groups and foreign touring companies; seeking out other aspiring writers, artists and musicians for intellectual discussion; and constantly writing”.

It was during the creative phase and experience-gathering in the 1920s, while working in his wealthy father’s provisions business, that he wrote pioneering stories as ‘One Day for John Small’, a short story about the commission agents, cocoa growers, businessmen and merchants, and personalities he was interacting with on a daily basis. Levy notes too that Mendes wrote about members of his own Portuguese ethnic group, and explored the expatriate society revolving around the colonial government.

Mendes published four slender volumes of poetry, wrote nine novels, and many short stories between 1920-1940. Levy tells us out of this body of writing, only 99 titles have endured. There were also two novels, Pitch Lake (1934) and Black Fauns (1935). Stories were also published in The Beacon between March 1931 and November 1933. Levy notes Mendes also published short stories in local and foreign magazines, many of which are extremely difficult to locate, or have totally disappeared. In 1940, Levy notes, “apparently in symbolic rejection”, and during a period of severe depression and economic hardship in New York, Mendes burned the manuscripts of seven unpublished novels.

He returned to Trinidad in 1940, and entered his journalistic phase. While working in the colonial civil service, he served as arts critic for the Trinidad Guardian, writing and (re)publishing stories in its Sunday supplement. Levy adds from 1966-1972, while working as personnel manager at Singer Sewing Machine Company, he edited the in-house publication the Trinidad Singer, in which he published his own stories. Mendes’ last significant writing was an autobiography, written during retirement in Barbados between 1975-1978, and published posthumously in 2002.

Sanders notes Mendes “in both theory and practice… insisted that West Indian writing should utilise West Indian settings, speech, characters, situations, and conflicts”. His first experiments in poetry “…failed dismally in indigenising this genre; consequently he destroyed most copies of a privately published poetry collection, The Wages of Sin and Other Poems (1925)”.

While Levy notes Mendes’ fiction was to some extent autobiographical, at the same time his “acute powers of observation and this propensity for transposing the experiences of his daily existence into his fiction, coupled with his prolific and varied output, make his an authentic voice in any attempt to understand and explicate Trinidad’s society in the 1920s and early 1930s”.

However, Mendes’ location in a colonial space also needs to be understood in its context of historical privilege, which was sharply hierarchal, stratified, and racialised. This is explored by Belinda Edmondson in Making Men: Gender, Literary Authority, and Women’s Writing in Caribbean Narrative. Here Edmondson quotes C.L.R. James, Mendes’ contemporary in the Beacon Group of writers that included writers Albert Gomes and Ralph de Boissière: “…Gomes told me the other day: ‘You know the difference between all of you and me? you all went away; I stayed.’ I didn’t tell him what I could have told him: ‘You stayed… because your skin was white; there was a chance for you, but for us there wasn’t – except to be a civil servant and hand papers, take them from the men downstairs and hand them to the man upstairs.’ We had to go, whereas Mendes could go to the United States and learn to practise his writing, because he was white and had money.”

Mendes was awarded an honorary D. Litt. from the University of the West Indies in 1972 for his contribution to the development of West Indian literature. He died in Barbados in 1991.

Sources for this exploration: Wikipedia; Fifty Caribbean Writers; The Man Who Ran Away; and, Making Men: Gender, Literary Authority, and Women’s Writing in Caribbean Narrative.