April 17, 2019 issue

Authors' & Writers' Corner

I am an ardent viewer of cricket on TV and was rather surprised to see a field of play with the players and the umpires, dressed in white – a format from the “good old days” of test cricket which still exists – a ghostly reminder from a glorious past.

I played cricket, dressed in white as a young man playing for my school team St. Stanislaus College in Georgetown, British Guiana. I also played for an RAF team in Somerset, England, but never got off the mark as a batsman! I can’t understand why they continued to select me, perhaps because I am a West Indian.

I have kept up with the sport, as best I can, living in Canada. I have read a number of the old books – The Freddie Trueman Story (Fiery Freddie), Blasting for Runs - Rohan Kanhai, John Arlott – Basingstoke Boy (famous cricket commentator), West Indian Test Cricketers (History of West Indian Test cricketers), and others, too numerous to name. I even have a few autographs of Test players. I also threw my hat into the ring when I wrote a chapter entitled Cricket Lovely Cricket in my novel Walk Good Guyana Boy (1994).

Test cricket seemed to be dying a slow but sure death. The defensive tactics, the long hours (five days), interference by weather conditions, the cost to maintain grounds, stands, clubs and equipment with declining finances, is a burden too hard to bear. One day cricket, known as limited over cricket of 50 overs, was first played in India in 1951 (Wikipedia). It became increasing popular over time and is still popular today, being played at all levels including the international level.

T20 cricket has marched on since its inceptions and is played internationally around the world in cricketing nations and also countries like Canada and the USA. Limited overs cricket -T20 and 50 overs (one day), are played day or night, or day and night, white balls, spot lights, cheerleaders, lots of hoopla, gate prizes, colourful player outfits with advertisers names on, and wild cheering crowds in packed stands, quite unlike test cricket (red ball).

Television transmits these games around the world. The players are paid high salaries and bonuses compared to the old days of cricket, including test cricket, when a player could hardly make a living from the game. The International Cricket Council (ICC) has granted T20 status to all 105 members from January 1, 2019 (Wikipedia).

The game has been improved by video assisted recordings to assist the umpire in the field in making decisions. The umpire sometimes wears a helmet for protection, not necessarily from the fans, but from the fast flying balls when he has to duck or run from big hitters and fast throwing fielders. Batsmen and other players wear helmets and body protection, a lot better than the “seed box” used in my time at bat. You need it with the balls flying at 90 miles an hour providing “chin music” for the batsman.

The players are trained to dive and hurl themselves around the field to stop and catch balls, unlike the old days when a player did his best to preserve the colour of his whites or flannel pants. The big old heavy white cricket boots have been replaced by much better athletic cricket shoes. By the way, if you have a pair of the old white boots, it can fetch a price on the internet.

I played my last cricket match about two decades ago in Markham, outside of Toronto, representing St. Stanislaus Old Boys against Queen’s College Old boys in a friendly game. I am proud to say that I opened the batting and was not out at the end of the innings. Some wondered whether two of my brothers who acted as umpires helped my cause (smile).

Cricket in all its formats has had its down side. Scandal, match fixing, unsportsmanlike conduct, poor umpiring, betting, drug taking, cheating and bribes, come to mind. Like all sport, these are issues that need on-going solutions. Cricket is not the gentleman’s game it used to be.

In my retirement, cricket has provided me with great entertainment. Together with football (soccer), they have helped me to while away many an hour, with memories of the sports golden greats, past and present. Soon, I will be called out to bat again, this time beyond the boundary. Hopefully, it will not be on a “sticky wicket”. If the creeks don’t rise and the sun still shines, I’ll be talking to you.

By Romeo Kaseram

Mahadai Das was born in Eccles, East Bank Demerara, Guyana in 1954. In her article , ‘Postcards from the Empire’, Gaiutra Bahadur, writing in Dissent, fills in some of the difficult to reach biographical details of Das’ short and tragic life. Bahadur tells us Das’ father was a rice farmer; that she was “both beauty queen (crowned Miss Diwali at seventeen at a Hindu festival in Georgetown, Guyana) and paramilitary volunteer (she donned fatigues and farmed cotton in service to a new nation reimagining itself as a ‘cooperative socialist republic’)… an Indian woman born in the West Indies, a granddaughter of indentured women”. Peepal Tree notes Das’ youthful, writerly calling, that she “[wrote] poetry from her early school days at Bishops High School, Georgetown”. Additionally, Das “did her first degree at the University of Guyana and received her MA at Columbia University, New York, and then began a doctoral program in Philosophy at the University of Chicago”.

Peepal Tree also tells us as a young poet, Das’ early work was published in several editions of KAIE, the official literary publication of Guyana's History and Arts Council. Writing in Caribbean Women Writers: Essays from the First International Conference, edited by Selwyn Cudjoe, Jeremy Poynting, in his paper, ‘“You Want to Be a Coolie Woman?”: Gender and Ethnic Identity in Indo-Caribbean Women's Writing’, notes Das’ first collection of poetry, I Want to Be a Poetess of My People (1976), contains “a few poems that survive the political sloganeering of the period” that deals with her Indian heritage.

However, a further exploration is undertaken by Denise DeCaires Narain, in Contemporary Caribbean Women's Poetry: Making Style, where she notes Das’ “active participation in the pro-nationalist initiatives of Forbes Burnham’s predominantly African Guyanese People’s National Congress Party” and her “enthusiastic involvement with the radicalism of the Burnham regime”. Narain tells us the collection “is propelled by a militant nationalism which Das uses to appeal energetically to Guyanese generally, and to women in particular”.

Narain notes one poem to be notable in this collection, ‘Cast Aside Reminiscent Foreheads of Desolation’, where its speaker “urges Indian women to refuse to see the future as predetermined by the traumatic past of indentureship and labour and to see the possibilities for ‘newer patterns of meaning’”. As Peepal Tree sums it up, while this first collection “traced the roots of the Guyanese people from indentureship to independence”, it also called “for a new sense of nationalism independent of colonial powers, though it also bears the marks of being beholden to the sloganising politics of the PNC”.

Peepal Tree adds by the time her second collection of poetry, My Finer Steel Will Grow (1982) was published, Das was becoming disillusioned with Guyana under the PNC and its corruption, authoritarianism, and anti-Indianism. Additionally, in this text, “Das speaks out about the discrepancy in fighting with men for racial equality, only to be suppressed by those same men in regards to gender”.

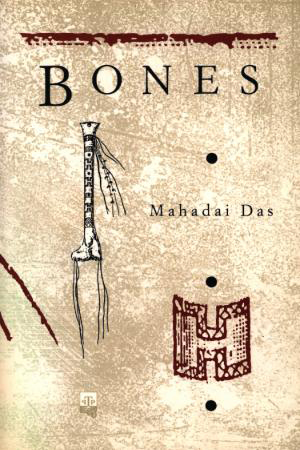

In her third collection, Bones (1988), among other things, Das addresses experiences as an Indo-Caribbean woman living in the urban US, where she seeks to recover the beauty of her cultural heritage within its materialistic culture.

Overall, Bahadur tells us Das’ oeuvre explores themes as “mortality, thwarted love, migration, postcolonial patriotism”. She adds: “Her poetry serves as an alternative imaginarium… illuminating a hidden chapter of colonial history from the perspective of those who suffered its wounds.” In a close reading of the poem, ‘Beast’, Bahadur notes Das’ direct engagement with indenture: “…pirates in search of El Dorado/ masked and machete-bearing/ kidnapped me./ Holding me to ransom,/ they took my jewels and my secrets/ and dismembered me./ The reckoning lasted for years./ Limbs and parts eventually grew:/ a new nose, arms skillful and stronger,/ sight after the gutted pits could bear a leaf./ It took centuries”.

Bahadur notes in this poem, “Das doesn’t explicitly mention the historical murders, but the machete that flashes between her lines evokes the violence against indentured women as well as the widespread plunder that accompanied colonialism”. Noting its historical antecedence, Bahadur tells us ‘Beast’ “refers to the first British encounter with the region, an explorer’s foray but also an imperial one: Sir Walter Raleigh was in search of El Dorado and its golden loot when he landed in the Guianas in 1594. In folk songs and stories told by the indentured three centuries later, the British in India feature as kidnappers of women, because they, even more than men, resisted recruitment as plantation labourers for a number of cultural and economic reasons. British seamen and overseers, who raped and exploited indentured women on ships and plantations, were literally and metaphorically responsible for stealing their ‘jewels’ and their ‘secrets’.”

Bahadur tells us Das also accuses the “European colonisers of doing some ‘dismembering’ of their own – severing the indentured from their country and kin, much like the Indian men who literally turned machetes against their partners.” It is through this imagery “of lost body parts that take centuries to recuperate” that Das “alludes to one of indenture’s most brutal legacies”.

The end of her life was untimely, “cut tragically short when she died of a heart attack in 2003, at the age of forty-eight”, Bahadur notes, adding, “Heiress to so much muted history, she was herself silenced in many ways. For more than a year after suffering a stroke, she lost her voice, described as ‘gentle but dangerous’ by a Trinidadian poet in New York who knew her.” Sadly, Bahadur also reveals that for a short time following her return to Guyana, Das lived in a car.

Summing up this remarkably short life, Bahadur tells us: “Published by her paramilitary unit and small independent and radical presses, Das’ work never reached a wider audience. But she remains a pivotal figure, one of only a handful of Indo-Caribbean female writers to emerge even now, a century after indenture’s end. A ventriloquist for our female ancestors, Das remains a rare voice in an otherwise silent archive.”

Sources for this exploration: Peepal Tree Press; Gaiutra Bahadur: dissentmagazine.org/article/postcards-from-empire; Caribbean Women Writers: Essays from the First International Conference; Contemporary Caribbean Women's Poetry: Making Style.