October 17, 2018 issue

Authors' & Writers' Corner

How important is rhythm? Rhythm can have different meanings but it is basically the length of time between each beat in music. Thus arises the question – What is beat? Beat is the basic unit of time in music. A strong beat, the downbeat comes first, incorporated into the rhythm of the music. In teaching dance, my wife and I have found a number of students with rhythm difficulties. This leads them to believe that they have “two left feet”. We have even discovered some musicians and DJ’s who seemingly have little sense or understanding of rhythm!

Rhythm is feeling the beat of the music, anticipating it and enjoying it. As Elvis used to say, “Let’s move it!” You go up and down with the music like you are surfing a wave, catching it and riding it for all it’s worth. Not everyone can be a good surfer, and similarly not everyone can be a good dancer.

A drummer, bass guitar, double bass, or rhythm section help the listener to catch the groove and be “in sync”. When you do so, you are ready to swing and soak up the sound. I let the sound flow through my body from head to toe. This perhaps is hard to explain in that you allow sound to “wash” over you. Where does it come from – the brain, the ears, your DNA?

It was once thought that drummers, who usually take their place at the back of a group, were the least talented, musically speaking. Anyone can make noise, critics say. Not so. Some studies indicate that drummers may have superior intelligence. Music engages many areas of the brain.

Can you teach a person to keep the beat? You can clap along, or stomp a foot, or use a metronome (time [beat] keeper), or listen to music regularly on the radio, or learn to play a musical instrument. However, we have found that in dance some students never seem to get it, in spite of how hard they try. The result is as they dance they trip themselves up or trip their partner. They simply dance to a different drummer. It seems that there is no cure for “beat deafness”. However some severely-hearing impaired folks can feel the beat and have learned to play musical instruments and to dance. How can that be explained?

Life is rhythm and rhythm is life. Listen to your heart – how well it keeps the beat faithfully over many years of life. There are many of our bodily functions that follow a pattern of regularity. There is a method of birth control that is called “the rhythm method” but it does not always work. The four seasons have their rhythms and patterns, the sun, the moon, the tides, each playing their part predictably for the most part.

In neuropsychological terms, beat deafness is called “amusia”. This is different from being hearing impaired or deaf. This is also different from tone deafness which is the inability to differentiate between “pitches” relative to the frequency of sound waves.

Music can affect emotions, movement, intelligence, learning, composing, creativity, dancing, singing and a host of other activities. The mysteries of music and rhythms continue to be unravelled. Good poetry usually has rhyme and rhythm. Music and language have close connections in the brain. Generally, the left frontal lobe, left parietal, and right cerebellum of the brain are all activated (Wikipedia). Some studies indicate that there may be difference in grey matter of professional musicians versus non musicians. This could have effects on levels of general intelligence, one can speculate. Musical genius never fails to amaze us.

If we can locate the beat center in the brain, perhaps we can activate it and correct it, the way we do with a timepiece like a watch, or the beat of a heart. One thing we have learned in working with students in dance is patience. I have often thought how lucky we are for whom keeping the beat is a natural activity, compared to others who struggle with this phenomenon throughout life. If the beat goes on, the sun still shines and the creeks don’t rise, I’ll be talking to you.

its own merit

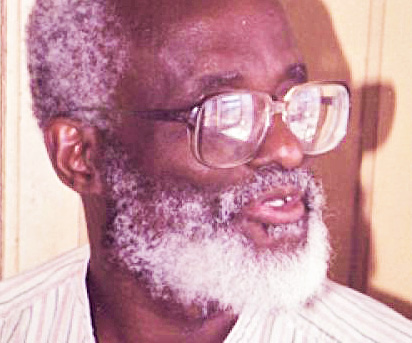

Biographical facts are difficult to come by about Garth St Omer, Roland E. Bush writes in Fifty Caribbean Writers, noting the author was a sensitive, self-protective artist who felt “very strongly that his work must stand on its own merits and speak for itself apart from any extraliterary authorial commentary or biographical intrusions from misguided critical assaults”. According to scattered biographical data, Garth St Omer was born in Port Castries, Saint Lucia, on January 16, 1931. The website, St Lucia Online, informs us St Omer graduated from St Mary’s College in 1949. It was at this institution where the young St Omer was likely inspired, having studied with the prolific writer, poet, and documenter of Saint Lucian history, Father Charles Jesse – details that are noted in the HTS St Lucia’s website, htsstlucia.org, and in the biographical outline in enotes.com. Additionally, according to enotes.com, Father Jesse served as a crucial mentor, likely recognising the budding artistry in the young St Omer. Later, St Omer would pay homage to Father Jesse, with a fictionalised representation in his first novel, where the priest plays chess with the protagonist.

Following graduation, St Omer taught for seven years at various Caribbean high schools. And according to Patricia Esmond, writing in the Encyclopedia of Post-Colonial Literatures in English, in 1956 St Omer won a scholarship to the University College of the West Indies in Kingston, Jamaica. He graduated in 1959 with honors in French and Spanish. St Lucia Online provides another nugget of elusive biographical detail: St Omer’s love for languages provided an early outlet for earning a living teaching English and French at high schools; and then again came another move to a distant shore, where he taught English and French at Apam Secondary School in the Gomoa West District of the Central Region of Ghana from 1961 to 1966. St Omer returned to Saint Lucia in 1966, there to devote himself to a career as a writer. However, yet again he traveled to foreign shores, as Osmond notes, this time to the US where St Omer earned an MA in Fine Arts from Columbia University in 1971, and a PhD in Comparative Literature in 1975 at Princeton.

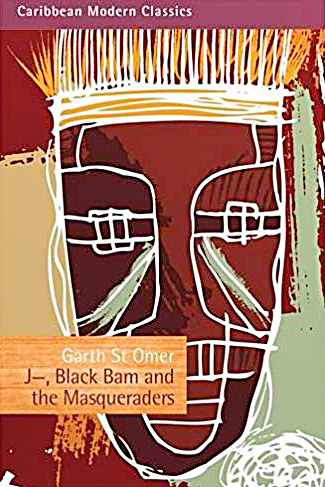

Osmond tells us among St Omer’s literary output are four related novels, A Room on the Hill (1968), Shades of Grey (1968), Nor Any Country (1969), J–, Black Bam and the Masqueraders (1972), and the novella Syrop (1964). The BBC’s radio programme Caribbean Voices broadcast six of his short stories; these stories were also published between 1951 and 1957 in the Caribbean journal Bim. According to Osmond, “St Omer has drawn critical attention for the power of his exposition of the identity crisis in which the Caribbean quest for self-definition began. The protagonist of each of his novels is an educated native son returning to his small-island environment, of which he remains very much a product. He drifts into a condition of futility and anonymity resembling that of the existential anti-heroes of Albert Camus and Jean-Paul Sartre.”

In commenting on St Omer’s craft, Bush says his “[Works] reveal a familiar complex of themes, conflicts, and even characters, consistently developed, elaborated upon, modified, and deepened effectively through an ever-increasing technical control and formal sophistication”. Bush also notes the comparative in St Omer’s novelistic structuring to be similar to the connected narratives of William Faulkner, James Joyce, Marcel Proust, and Thomas Mann. He adds: “Progressing in a style which tends to replace chronology and external reference with duplication and internal associations and formal determinants, these slim volumes continue uniquely to mine the fundamental themes of exile, identity, and alienation implicit in the entire body of Caribbean writing.”

Citing Gordon Rohlehr’s writings, Osmond notes this critic’s comparison of St Omer’s “technique of detached objectivity in presenting this essentially confessional material to the ‘scrupulous meanness’ of James Joyce’s Dubliners (1914)”. Osmond writes: “Joyce, in fact, has been the most important influence on St Omer at both the thematic and formal levels, inspiring him to render the native paralysis of his own St Lucian setting. St Omer’s early sense of the parallel between Joyce’s Ireland and that of his own poverty-ridden island – where more than 90 percent of the population is Roman Catholic – informs his penetrating criticism of Catholicism as a dominating colonising influence that imposes values remote from the lives of an already-deprived community.”

Among St Omer’s early literary output is the notable Syrop, which according to St Lucia Online helped to launch his writing career. Appearing as early as 1964, Syrop’s narrative is an exploration of a young African Caribbean man who loses his life to the propeller of a passing ship on the day he starts work. In exploring Syrop, Osmond notes that “St Omer's exploration of St Lucian paralysis involves a questioning of human purpose expressed through the large number of deaths in his novels. While this preoccupation has been linked primarily with the influence of the French existentialists, Syrop, written in the early 1950s, also has its origins in St Omer’s native environment. Syrop, whose name is the St Lucian French-Creole word for honey, is the one child who might sweeten the wretched life of old Deaies. In diving for coins to buy a welcome meal for his older brother, due to return from jail, Syrop is decapitated by the propeller of a ship. Syrop proceeds from life’s fatalistic extremes and questions an inimical, indifferent universe that mocks faith in humanism itself”.

In 2001, St Omer received The Saint Lucia Medal of Merit (Gold) from the government of Saint Lucia. He was also declared a cultural icon in 2017 by Saint Lucia’s Cultural Development Foundation during its Cultural Icon Series, in recognition for his work as a Saint Lucian literary pioneer. In its presentation, the foundation featured St Omer’s work in a two hour concert where a variety of artists interpreted his writing through dance, theatre, poetry, and music. He was also the recipient of the Ford Foundation Grant, and a Fellowship from the Department of Comparative Literature from Princeton University. He passed away on April 24 this year in Santa Barbara, California, where he had lived and taught for many years.

Sources: Fifty Caribbean Writers; www.stlucianewsonline.com/saint-lucian-icon-garth-st-omer-passes-on/; Encyclopedia of Post-Colonial Literatures in English; www.htsstlucia.org/ministry-of-equity-pays-tribute-to-dr-garth-st-omer/; and www.enotes.com/topics/garth-st-omer.