April 25, 2017 issue

Authors' & Writers' Corner

By Romeo Kaseram

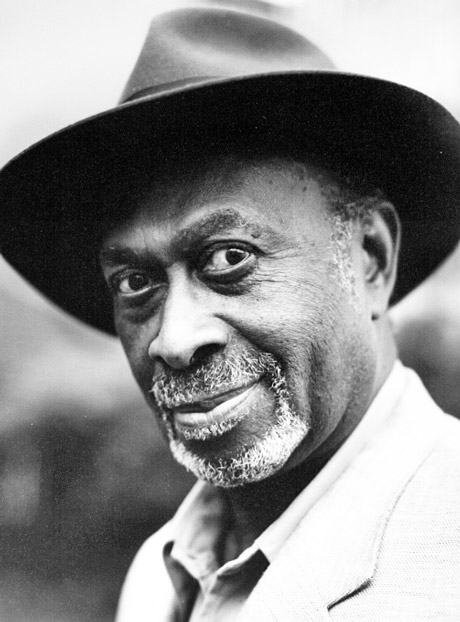

James Berry was born on September 28, 1924 in Fair Prospect, Jamaica the fourth of six children to parents Robert, a smallholder, and mother Maud, a seamstress. The family relied on subsistence farming and the sea, and late in life, Berry would recall helping his father with the fishing nets. As a young boy he had learned to read before he was four, and as a teenager, he knew there was no future in Jamaica after leaving school at 14. Following his education, he worked through several small and itinerant jobs, among them being a shoemaker, a tailor, and a travelling medicine salesman, before leaving Jamaica in 1942 for the US, where he worked for six years as a contract labourer on farms and in factories. Speaking to Ian Thomas in Black History Month in 2015, Berry recalled this early move: “America had run into a shortage of farm labourers and was recruiting workers from Jamaica. I was 18 at the time. My friends and I, all anxious for improvement and change, were snapped up for this war work and we felt this to be a tremendous prospect for us. But we soon realised, as we had been warned, that there was a colour problem in the United States that we were not familiar with in the Caribbean. America was not a free place for black people. When I came back from America, pretty soon the same old desperation of being stuck began to affect me. When the [SS Empire] Windrush came along, it was godsend, but I wasn't able to get on the boat... I had to wait for the second ship to make the journey that year, the SS Orbita.”

The now famous SS Empire Windrush sailed in June 1948, opening up the largest movement of Caribbean people to Britain, what is now known as the Windrush Generation. It was followed a year later by the SS Orbita, which arrived in Liverpool, England, in September 1949 – Berry was on board with the other 107 migrant Jamaicans seeking out a better life. However, before getting there, he spent his first night in London at the Salvation Army hostel. As Berry later wrote, which is quoted by Oliver Holmey in the Independent in 2017: “Here we were, hating the place we loved, because it was on the verge of choking us to death”, his statement yielding an insight into what the young man took with him to Britain – an ambivalent mix of emotions, what Holmey further describes as “a love-hate relationship with his childhood home, along with the hope of a new life in a foreign, at times unforgiving, land”. Holmey notes this mix “would come to inspire much of his poetry, establishing him as one of the most prominent black voices in contemporary British literature”.

Berry as a young migrant soon found work as a Post Office telegraph operator, and continued in this role for more than two decades, ending this career in 1977. He was also writing poetry at this time. He was an early member of the Caribbean Artists Movement, which was founded in 1966 by Edward Kamau Brathwaite, Andrew Salkey, and John La Rose. He became the group’s acting chair in 1971. Living in Brixton with its crowded living conditions and racist attitudes drove him into writing and publishing his first poems, which appeared in small magazines. Berry also formed a poetry performing troupe in 1972, called the Bluefoot Travellers: the word, “bluefoot” was his neologism, a pejorative Creole word meaning, “outsider”. His first poetry collection was Fractured Circles (1979), which was published by La Rose’s company, New Beacon Books. Prior to this, in 1976 he compiled the anthology Bluefoot Traveller. He won the Poetry Society's National Poetry Competition in 1981, the first poet of Caribbean origin to do so. In 1984, he edited the anthology News for Babylon. Berry also wrote many books for young readers, among them A Thief in the Village and Other Stories (1987), The Girls and Yanga Marshall (1987), The Future-Telling Lady and Other Stories (1991), Anancy-Spiderman (1988), Don't Leave an Elephant to Go and Chase a Bird (1996) and First Palm Trees (1997). In 2011 he published A Story I Am In: Selected Poems (2011), which drew from works from his five earlier collections: Fractured Circles (1979), Lucy’s Letters and Loving (1982), Chain of Days (1985), Hot Earth Cold Earth (1995), and Windrush Songs (2007).

Writing in The Guardian in 2017, Alastair Niven notes Berry was one of the best-loved and most taught poets in Britain, a great champion of Caribbean culture, an influential anthologist, and a determined though unsentimental advocate of friendship between races. He adds Berry’s poems “ranged from the lyrical to the caustic, but almost all of them intimately caught the speech patterns of his native Jamaica”, and he “helped to enrich and diversify the capacities of the English language, making conversational modes of West Indian expression, which a previous generation would have considered exotic or barely literate, normal and easily understood”.

Holmey notes Berry’s voice was distilled from exposure at a very young age to “two distinct tongues: on the one hand, the ‘standard’ English of the Bible and of Sunday prayer books; on the other, the tunes of everyday Jamaican. Both… would permeate his work”. He adds: “Berry did much experimentation with form, writing folk proverbs, rap lyrics, conversations, haikus and, in a series of poems that particularly suited him, fictional correspondence… But what distinguished him was his ability to write beautifully both in ‘standard’ English and in Creole, choosing one or the other, or sometimes interweaving the two in a single text. This style of his, he said, ‘simply emerged naturally’. But it was of great significance to Caribbean writers of his generation and the next, as it further legitimated Creole as a form of poetic expression.”

Berry won numerous prizes throughout his lifetime – the Smarties prize in 1987; and the Signal poetry award and the Coretta Scott King book award in 1989. He was appointed OBE in 1990, and received a Cholmondeley Award in 1991. He was made an honorary fellow of Birkbeck College, London, in 2001, and was awarded an honorary doctorate by the Open University in 2002. The last six years of his life was spent in care, and he passed away on June 20, 2017 after suffering from Alzheimer's disease.

Sources for this exploration: Wikipedia, British Council; The Guardian; and The Independent.

to ‘Mr Fix It’

Those of us (seniors plus) in “the twilight time “, often realize that time is a dwindling commodity. How do we spend our time and money (if we have any)? A number of folks, having reached retirement, go back to work full time or part time, out of necessity or boredom. Retirement does not come easily to many people, in spite of the fact that they probably spent many years saving for and looking forward to their retirement.

For me the choice was not difficult. The freedom of doing what I want to do, going to places I often wanted to see, dressing in whatever pleased me, not having a boss to report to, – sleeping and eating whatever and wherever I wanted. I grew my hair long, danced a lot, and developed new and satisfying hobbies, enjoying the traditional “Freedom 55”. You might say I became an elderly, new generation “hippy”. Fortunately I have a wife who went along with me for the ride.

A number of folks continue to worry about having money for retirement and are hounded by “investors” willing to put their hands on retirees’ nest eggs and turn them into gold! More likely than not it is the investors who turn into gold. When the investments fall flat as in a financial collapse, the poor retirees exclaim ‘All gone Lake”, a generalized quote from an infamous Guyanese murder trial.

I believe that folks should spend more time in investing in their health and well being. To retire to boredom, inactivity and counting your dollars is to sign your death warrant. Many worry about dying when they should be thinking of living. A number of folks with lots of money don’t have the health to enjoy their wealth nor are they prepared to help others with their money, not realizing that there are no pockets for their possessions in the coffin. At least, last time I looked.

For decades my wife and I have contributed to Plan International, formerly (Foster Parents Plan of Canada). Their work of helping children and their families in some of the most impoverished places in the world through improvements in health, education, housing, water supply, and basic needs have given generations of children a chance at a much longer and better life.

Some folks are skeptical about charities and where the money goes and sometimes rightly so. Doing your own research and personal evaluation, you can find a charity or volunteering organization that suits you. Habitat for Humanity is an organization that helps people build decent and affordable homes. One can hardly call donating to building Trump’s wall a good charity and a place to start volunteering!

Many people think that the less fortunate are not our problem. Let the politicians fix that. That is fine, but first we have to fix the politicians. There are problems to be solved. Let us at least try. Let’s become part of the solution rather than part of the problem. One of the things I learned in studying for my doctorate is that a problem cries out for a solution. Questions demand answers. Where there is a will, there is a way.

I have found that with retirement I have become more of a problem solver and better at fixing things. I now term myself “Mr. Fix it” around the house and yard. My wife does not call me “Ten Thumbs” any longer. Her reaction to things that get broken is usually “Throw it away!” I say, “I’ll fix it.” In more than half the cases, I do fix the item, even if it is only a temporary fix. Unfortunately my wife wants a permanent fix at all times. I now have many items on the waiting list to be fixed or re-fixed.

There are times when things go south as they say and we can’t fix everything. However, as Michelle Obama has said “when they go low, we go high.” . We have choices in life. No man is an island. When I told a sibling of mine that I was “a citizen of the world”, he looked at me with astonishment. The concept was totally alien to him. Let us use the time we have left for healthy and helpful pursuits. If the creeks don’t rise and the sun still shines I’ll be talking to you.