September 20, 2017 issue

Authors' & Writers' Corner

Bernard Heydorn

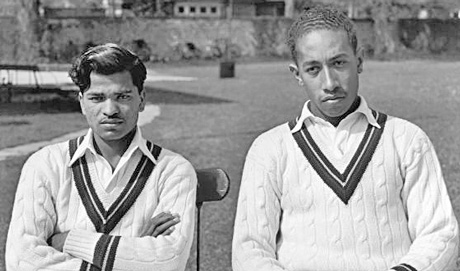

Cricket, and particularly West Indian cricket, seems to be enjoying a type of Renaissance. Although one swallow does not a summer make, the West Indies in their recent tour of England made a Houdini type dramatic come- back in the second test at Headingly. After their embarrassing loss to England in the previous test when they lost 19 wickets in one day, no one envisaged their comeback in the Headingly test. Previous to this, the West Indies had not won a test match in England for 17 years! Sadly they then went to Lords in the next test and lost again, thus losing the series 2-1.

Cricket, be it test, county, or regional seemed to be in steep decline. Furthermore, the great West Indian test sides looked long gone. The only form of the game that looked promising was T20 and one day 50-over games. The young West Indian Test team in England was filled with relatively unknown names. Many of the players were unfamiliar with English conditions, with the ball seaming and swinging every which way. It had the West Indians tied up in knots. The English commentators were saying that the test series would provide the English batsmen with batting practice in preparation for the Ashes tour in Australia in the Fall.

The test match scene had sunk to such a level that on the last day of the Headingly test they were virtually giving tickets away, free for children and 10 pounds for adults. Compare that to the cost of attending a Premier League football match in England, if you can even get a ticket to buy without being a season-ticket holder.

The new group of West Indian cricketers rose on the shoulders of Shai Hope who scored centuries in each of his two innings, a record for the Headingly ground in its long history. Kraigg Braithwaite also scored a century and came very close to scoring a second. The gallant bowlers and big-hearted captain Jason Holder played their parts. Shai Hope ironically, had only scored 18 test runs in 11 matches previous to this! There were a number of dropped catches on both sides, what some called the curse of Headingly, but that only added to the drama taking place on the field.

Some are saying that the Test win was only a fluke for the West Indies. They will go back to playing recklessly and undisciplined cricket without the confidence needed to win. Some suggest that there will continue to be problems and disputes between the players and the West Indian Cricket Board. Only time will tell.

This summer, I watched the Women’s World Cup cricket and thoroughly enjoyed it. The skills and dedication shown by the ladies were a delight to see. The exposure of their game to TV the world over did wonders for them and the game. It certainly gave the game of cricket a shot in the arm.

Cricket perhaps will live on with the help of its different formats. The West Indian team can now start to rebuild with new legendary figures, heroes to young and old coming from their ranks, rising from the ashes of the last 20 years. They have a long way to go being ranked 9th and last in the current ICC Test Rankings. The game can then become “cricket lovely cricket, at Lords where I saw it,” as the calypso singers sang. If the creeks don’t rise and the sun still shines I’ll be talking to you.

By Romeo Kaseram

Phyllis Byam Shand Allfrey was born on October 24, 1908 in Roseau, Dominica, to parents Francis Byam Berkeley Shand and Elfreda (née Nicholls). Her father, the prestigious Crown Attorney, descended from settler stock long established in Roseau, part of the white elite dominating Dominica for over 300 years. According to Wikipedia, Allfrey’s family roots go as far back to the 17th century with ancestors including Henry Spencer Berkeley and Sir Thomas Warner; on her father's side was the relation Dorothy Knollys, the great-great-great granddaughter of Mary Boleyn, Anne’s sister to the royal family in England. Allfrey’s mother was one of the daughters of Sir Henry Alfred Alford Nicholls, a doctor and botanist also with family ties to royalty. Allfrey’s maternal grandmother from Martinique, Marianne Felicite, was related to Napoleon's Empress Josephine. Further linkages connected Allfrey to the Belgian, Luxembourg, Swedish, and former Romanian monarchs. With such an interconnected genealogy, it meant Allfrey and her family were closely related to royalty from Belgium, Greece, Russia, Brazil and Luxembourg; also, on both her father’s and mother’s side the linkages were traceable to British royalty through the Danish and Greek descent of Empress Josephine.

The value and eminence of such an extensive network to elite bloodlines was not lost to Allfrey. As Lizabeth Paravisini-Gibert writes in Phyllis Shand Allfrey: A Caribbean Life, [Allfrey’s] “family’s illustrious lineage was the source of a profound pride that was an integral part of her upbringing and profound sense of obligation to the West Indies. One of her most cherished possessions was Antigua and the Antiguans: A Full Account of the Colony and Its Inhabitants from the Times of the Caribs to the Present Day, an 1884 work which details the genealogy of the Byam-Shand family to that date, and to which she had added in her own hand the names and birth dates of the generations that followed”. Her elitism in Dominican society was not lost to Allfrey, even as a child. Writing in The Guardian in 2005, David Dabydeen cites Allfrey’s place in the world being dictated by her father, who, “by her own account, was hostile to black Dominicans”. Dabydeen continues: “‘He kept his family apart from other races,’ she wrote, and Allfrey was denied formal schooling to prevent encounters with Catholics or people of colour who would soil her purity. She was taught privately at home, reading works such as the Oxford Book of English Verse, Rupert Brooke's poetry, and English Pastorals. The lush Dominican landscape, loud with Creole voices, was shut out from literary appreciation. Her father’s house was a piece of foreign fields that was forever England… She was a scion of privilege, moving with the wealthy white visitors who anchored their yachts in Dominican waters. The American millionaire banker JP Morgan was a family friend, and through his patronage Allfrey was able to leave Dominica as a teenager and live in New York and then London, where she met and married an Oxford graduate [Robert Edward Allfrey].” Allfrey left Dominica for New York on the Morgan’s luxury yacht.

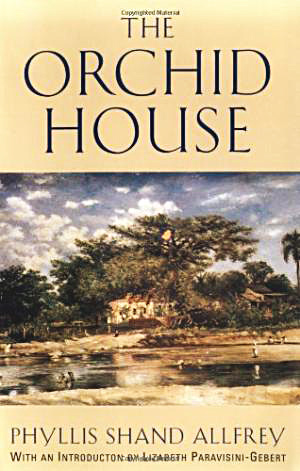

It is understandable, then, why as Dabydeen recognises, there “was nothing in Allfrey's childhood and youth to suggest the trail-blazing radicalism of her later life”, this change taking place following “her encounter, in her transatlantic travels, with the depression in America, and then with the emerging Labour party in 1930s Britain”. Dabydeen points to these events as the decisive moments that changed the course of Allfrey’s life, and which marked her awakening to socialist struggle. So it was that Allfrey became engaged “in welfare and grassroots work (including giving support to her fellow Dominican Jean Rhys), as well as the international campaign on behalf of the Spanish Republican cause” in London in the 1930s and 1940s. It was in this time when Allfrey wrote most, among these short stories and poetry in which she rediscovered the Dominica of her childhood. It is in these works where Dabydeen notes Allfrey “striving to capture the flavour of creole life that had been denied to her” during early life. Such was the quality of her work, the novelist and essayist, George Orwell, then editor of the left-wing Tribune, published some of Allfrey’s writing; her writing also appeared in the Manchester Guardian. Allfrey was awarded a literary prize by the English novelist and poet, Vita Sackville-West; then 1953 saw publication of her major work, The Orchid House.

According to Dabydeen, The Orchid House explores “the racial situation in Dominica, and [is] about the emergence of feminism as well as the beginnings of the political agitation that would put an end to the old order. In the novel the black person is given a central voice, black aspirations are given rare expression”. The Encyclopedia of Post-Colonial Literatures in English notes in the novel, “As well as evoking the total society, Allfrey sharply criticises the Roman Catholic Church, which is seen as rigid, conservative and stifling… [It] succeeds in avoiding the promotion of a single group, the clichés of race, colour, class and tourist landscapes, didacticism, bitter flourishes and wooden allegorical characters.”

To have arrived at this point in her life meant Allfrey had come to understand what post-colonial scholars as Homi Bhabha and Gayatri Spivak would later call unhomeliness, hybridisation, and double consciousness, in this case Allfrey being a mix of elitism and privilege while simultaneously contained inside a marginalised, colonised space. As Dabydeen notes: “The irony of course was that the shaking-off of the shackles of colonialism would also mean the shaking-off of Allfrey herself, but she still embraced the cause of nationalism.” So it was, Allfrey returned to Dominica in 1954, where she founded the Dominica Labour Party. Winning the 1958 elections by a landslide, she was appointed minister of health and social affairs in the Federation of the West Indies. Following the collapse of the federation, she then struggled with identity politics seeking to push her into the margin. Her later life saw major personal turbulence and setbacks, with the loss of her house to Hurricane David in 1979, and the tragic death of her daughter in Botswana.

Along with politics, these tragic moments impacted greatly on her writing. However, as Dabydeen notes, “sufficient work remains to allow us to appreciate her talent and her contribution to West Indian literature. The 14 short stories now gathered together under the title It Falls Into Place exemplify what the writer Olive Senior calls ‘her delicate touch, discerning eye and heart wise to the human condition’. Her true virtue, however, lies in her intense, almost overpowering feeling for the West Indian landscape, reminiscent of the qualities of Rhys's Wide Sargasso Sea”.

Allfrey died February 4, 1986, the last 20 years of her life, which in Dabydeen’s words were “lived in acute poverty”.

Sources for this exploration: Wikipedia, The Guardian, Encyclopedia of Post-Colonial Literatures in English, and Lizabeth Paravisini-Gibert’s, Phyllis Shand Allfrey: A Caribbean Life.