February 15, 2017 issue

Authors' & Writers' Corner

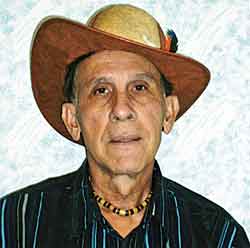

Bernard Heydorn

Bisca pronounced "Bishkuh" in Portuguese is a card game of Portuguese origins. This I discovered on my revisiting Portugal. When I was a child growing up in British Guiana my parents and family played "Bishkuh" regularly at night with friends and neighbours. No one knew or even mentioned anything, to the best of my knowledge, about "Bishkuh" having Portuguese connections. Bishkuh and Whist seemed to be the most popular card games.

Wikipedia refers to Bisca as the Portuguese variation of the Italian card game Biscola. Bisca is reportedly

Players developed their own favourite suit. My father disliked spades and particularly the ace of spades. In creole he called it something sounding like "bush". It was derogatory to describe someone "as black as the ace of spades". There is a lot of superstition surrounding the ace of spades which is considered the "death card" or bad luck in some cultures. I have no strong preference except perhaps for hearts. They look bright and cheery.

The game is played by following suit or trumping if you have no cards of the suit led. A trump is pulled right after the cards are shuffled and before they are dealt to the players. The tradition was to deal five cards to each player and play clockwise. Four or more can play as couples or teams. You can also play as individuals with two or more players, as far as I recall.

Bisca is a game that seems to depend more on luck than skill. It is a game enjoyed by people "killing time", retirees, old folks, bored folks, poor folks (cards are cheap), folks on vacation, and just about anyone from children to adults, hence its popularity. The game is played quickly, 15 minutes or less, hence it can be seen in bars, clubs, restaurants, hotels, airports, train stations, and cruise ship.

Some folks are really fond of Bisca, like my older sister, who seems to win most of the time. One can easily become addicted to the game. My parents used Bisca to socialize at night, inviting friends and neighbours to participate at our home.

They gathered around the dining room table in the little house in New Amsterdam, with the solitary 60 watt light bulb illuminating the scene. Moths, bugs (some giant size), hard back black beetles, and home grown mosquitoes from Crab Island just outside of New Amsterdam, fought for the attention of the light. If a beetle called "cockle" happened to find its way inside a female top, the game would abruptly stop and the offender would be removed unceremoniously.

My father enjoyed being the grandmaster at these games. He was the loudest and called the shots, barking, "Third man play his best!" "Ah got a hand like a foot!" He might wink at a partner or touch a foot under the table to signal to his partner to play a card in the same suit or to trump. It was all tricks of the trade.

Half way through the evening, around 9 o'clock, he would announce an intermission break for drinks and biscuits. My mother would serve up the refreshments and I would help by taking them around. Two bottles of Ju-C would be split among the guests in small glasses and if there was anything left over, I would get it in a schnapp glass used for alcoholic drinks. I then returned to watch proceedings from a small crack in the bedroom door. Every seat was used up in the house, including some drinks crates.

The invited guests were men and women my father was on good terms with, including folks of some shading or colour. In those days there was no tv, little money, no computer, no smart phone, just radio and a "fowl house" cinema, for entertainment. Some in the higher class of society had their private clubs and played games like billiards. These were usually the "high whites" and those aspiring to be white.

I can imagine the Portuguese emigrants from Portugal and Madeira in the 19th century, on their sailing ships heading for Guyana playing their Portuguese guitars, singing folk songs, and playing Bisca to pass the time on their long journey. They brought their traditions and culture with them including card games, and passed them on.

I believe that folks from other cultures and backgrounds played Bisca in Guyana in the old days, perhaps even today. The two games I remember best are Bisca and dominoes, which are very popular in the Caribbean. Perhaps I can start a Bisca Club in Canada and remember the old times and the old folks at home as I enter the twilight years. If the creeks don't rise and the sun still shines I'll be talking to you.

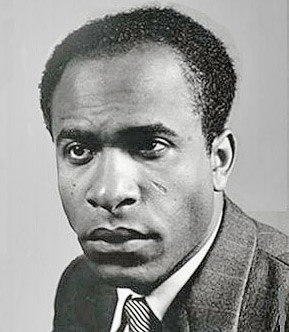

By Romeo Kaseram

Frantz Fanon was born in the French colony of Martinique on July 20, 1925, to father Félix Casimir, a customs inspector, and mother, Eléanore Médélice, who owned a hardware store in downtown Fort-de-France. His father was a descendant of African slaves and the indentured East Indians, with his mother of black Martinican and white Alsatian heritage. Fanon was the youngest of four sons in a family of eight children. Two of his siblings died in childhood.

The family was middle-class, occupying a social position within Martinican society at a level where they could be assimilated and identify with the white French culture. Growing up in such an environment, Fanon’s early schooling was learning French history on his own. However, the family was wealthy enough to be able to afford the fees for the Lycée Schoelcher, which was then the most prestigious high school in Martinique. It was here where he met the writer Aimé Césaire, who was one of his teachers. Also, it was in his high school years when he first encountered the philosophy of negritude, taught to him by Césaire.

By then World War II was being fought in Europe. The young Fanon found himself torn between the longings of Martinique’s middle class and his preoccupation with Césaire’s teachings surrounding negritude and racial identity. He left Martinique in 1943, when he was 18 years old to fight for France in the dying days the war. There he enlisted in the Free French army, joining an Allied convoy that stopped at Casablanca. Later he was transferred to an army base at Béjaïa on the Kabylie coast of Algeria. Following this, he left Algeria to serve in France, where he fought in the battles of Alsace. He was wounded in 1944 at Colmar, and received the French military decoration, the Croix de Guerre.

It was during the war when Fanon found himself exposed to anti-black racism. For example, following the defeat of the Nazis, as Allied forces crossed the Rhine into Germany, Fanon’s regiment was “whitened” with the removal of all its non-white soldiers. Fanon, along with other Caribbean soldiers, were sent to Provence, and were later transferred to Normandy, following which they were repatriated to the Caribbean.

He returned to Martinique in 1945, where he worked on the parliamentary campaign for Césaire, who was now a good friend and mentor. Césaire was running on a communist ticket as a parliamentary delegate from Martinique for the first National Assembly of the Fourth Republic. Fanon remained long enough in Martinique to finish his degree. Following this, he returned to France to study medicine and psychiatry. He studied at the University of Lyon, where he also pursued literature, drama and philosophy. In this time he wrote three plays.

It was at the University of Lyon where Fanon began encountering more intense anti-black racism. Out of these experiences came the inspiration for ‘An Essay for the Disalienation of Blacks’. From this writing would emerge one of his main works, Peau Noire, Masques Blancs in 1952 (Black Skins, White Masks). It was also during the University of Lyon years where he began his exploration of the Marxist and existentialist ideas that would lead to a departure from the assimilation-negritude dichotomy he felt in Martinique.

Qualifying as a psychiatrist in 1951, Fanon worked on a residency in psychiatry at Saint-Alban-sur-Limagnole, where he met the Catalan psychiatrist François Tosquelles, who introduced him to the role of culture in psychopathology. Following his residency, Fanon practiced psychiatry at Pontorson, near Mont Saint-Michel, and then from 1953 at the Blida-Joinville Psychiatric Hospital in Algeria. The following year saw the start of the Algerian war of independence against France. It was an uprising directed by the Front de Libération Nationale, and this was brutally put down by French armed forces. While working at the hospital, Fanon treated soldiers and officers of the French army for psychological distress. These were the individuals behind the torture being used to suppress the anti-colonial resistance. Fanon also treated Algerian torture victims. In 1956 he decided he could no longer aid French efforts to put down the movement, and he resigned his position at the hospital.

Fanon then devoted himself to the cause of Algerian independence. In this time he was based primarily in Tunisia where he trained nurses for the FLN, edited its newspaper el Moujahid, and contributed articles about the movement to publications such as Presence Africaine and Jean-Paul Sartre’s journal Les Temps Modernes. Some of his writings from this period were published posthumously in 1964 as Pour la Révolution Africaine (Toward the African Revolution). In 1959 he published a series of essays, L’An Cinq, de la Révolution Algérienne, (The Year of the Algerian Revolution), detailing how the people of Algeria organised themselves into a revolutionary fighting force.

Also in 1959 he took up an appointment to a diplomatic post in the provisional Algerian government as its ambassador to Ghana. It was in Ghana where he was diagnosed with leukemia. Despite his decline, Fanon spent ten months of his last year of life writing the book for which he would be most remembered, Les Damnés de la Terre (The Wretched of the Earth). This text would become an indictment of the violence and savagery of colonialism. Its culmination is a call for a new history of humanity to be initiated by a decolonised Third World.

Black Skin, White Masks is one of Fanon’s most important works. In his discussion of language, for example, Fanon speaks to a black person’s use of a coloniser’s language being seen by the coloniser as predatory and not transformative; this in turn could lead to insecurity in a black person’s consciousness. He is also well-known for the classic analysis of colonialism and decolonisation in The Wretched of the Earth, which was first published in 1961 with a preface by Jean-Paul Sartre. In this book, Fanon analyses the role of class, race, national culture and violence in the struggle for national liberation. The writings in both books established him as a leading anti-colonial thinker in the 20th century.

Fanon died on December 6, 1961. His body was returned to Tunisia, then taken across the border and buried in Algeria. He was survived by his French wife Josie (née Dublé), son Olivier Fanon, and his daughter from a previous relationship, Mireille Fanon-Mendès France.

(Sources for this exploration were Britannica, Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, and Wikipedia.)

(Sources for this exploration are Margaret Bushby’s 2014 eulogy published in the The Guardian, Wikipedia, Stabroek News, and , ‘Race, Colour, and Class in Black Midas’, published by Dr. Frank Birbalsingh in 2002.)