April 19, 2017 issue

Authors' & Writers' Corner

Bernard Heydorn

As Easter rolled around once more, I began to further realize why it is such an important feast in the Christian calendar. Listening to the Passion of Jesus, his crucifixion and death at a recent Palm Sunday mass I attended, I could not help but reflect on the events and their relevance to today’s world.

Christmas and the birth of Jesus are celebrated more widely compared to Easter it seems. I have written many times about Christmas but little about Easter. It’s not that Easter goes unheralded. Think about Easter eggs, and egg hunts, very popular in our household when our children were

Easter Sunday appears on different dates each year. It is often manifested in church services filled with parishioners. Many used to dress up in their “Sunday best” in the old days in Guyana when I was growing up. Many faces would disappear until the next Easter when they would show up for a blessing and the removal of sins. It’s not certain where the word Easter comes from but it does seem to have historical roots.

I enjoyed the hot cross buns (buns with a cross on top) and still do. I remember the song “One a penny, two a penny; hot cross buns”. Barbadians went a step further and put black pepper on their cross buns calling them hot cross buns. Coming at the end of Lent and fasting, Easter is truly a celebration. The statues in churches, covered during Lent, are uncovered in triumph.

Some of the details of the trial, crucifixion, and death of Jesus really stuck with me this year. The relevance of what Jesus faced over two thousand years ago, seems all the more relevant in today’s world. The different factions of society and religion, political unrest, jealousy, power struggles, lies and fabrications, betrayal, the post truth era, the faithless, wars and rumours of war, torture and death, good existing in the midst of evil… It’s all there and more.

The supernatural is evident with the sudden darkness while Jesus was on the cross, “the veil of the temple being rent from top to bottom, the earth quaked and the rocks were rent, the graves opened and many bodies of the saints that had slept a long time arose,” according to the scripture.

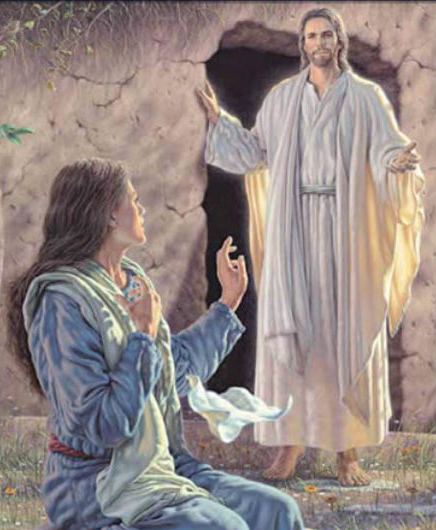

The vigil of the faithful Mary Magdalene and the other Mary sitting by the tomb of Jesus are heart stirring. The breaking of the sealed and guarded tomb and the resurrection of Jesus after three days are all high drama that gives me the chills!

For us older folks, the death and resurrection of Jesus are perhaps even more relevant. We who sit and watch on “the graveyard shift” can’t help but wonder what lies ahead. If the creeks don’t rise and the sun still shines, I’ll be talking to you. Have a Happy Easter with friends and family.

By Romeo Kaseram

(Part One)

Harold Sonny Ladoo was born in McBean Village in central Trinidad. More specific biographical details are sketchy, and to explore Ladoo’s life is to encounter mostly anecdotal recollections from his friends, colleagues, and peers here in Canada. It is such that only a limited picture (and a mostly unfulfilling and bleak one at that) can be recreated of Ladoo’s short and tragic life.

We are given a glimpse into Ladoo’s early life by a mentor and friend, Peter Such, in his moving and elegiac essay, The Short Life and Sudden Death of Harold Ladoo: “He was born out of the pressure of wartime. Sometime around 1945 in Trinidad. One of his stories recounts a rape-murder by Americans from a nearby base and the helplessness of the peasant father in the face of the bribery and intimidation of the hush-up. Maybe he was born earlier. The insurance company noted ‘proof of age not accepted’ on a small policy he took out. His birth certificate was a colonial relic, many-columned and hand-written in the English style. It was hard to decipher, and only one name on it seemed to relate to him, ‘Soni.’ There was also the notation, ‘Illegitimate.’ I could imagine the colonial bureaucrats shaking their heads, trying to make good clean Christian order out of it, muttering about these damn illiterate natives. At the level of marriage certificates they probably gave up completely.

“He grew up in the plantation area of Couva, near the small village called McBean, with a family called ‘Ladoo.’ This is the part of the Island nobody visits unless they were born there. The population is descended from indentured labourers from India who were imported to replace the supply of African slaves when slavery was abolished.”

Such recalls his first meeting with Ladoo: “I first met Harold Sonny Ladoo at the Islington subway station, waiting for a bus with a crowd of Erindale and Humber College students. He was huddled in a cheap coat too large for him: black hair, thin dark face, small moustache, large dark eyes staring straight ahead, looking at somewhere else completely. I noticed he was jotting words down on the back of a TTC transfer. It could have been a shopping list he was writing, an address, anything. But I had a strange and certain feeling I knew what it was. I’d done exactly the same thing myself. I said, ‘Hi. You're a writer, aren't you?’ He said, ‘Yes.’ We had a coffee together and I explained I’d just been given a job as writer-in-residence at Erindale. He was interested to hear that, since he felt a university would be a good place to get in touch with the world's great literature, and besides, there'd be all these wise men to converse with. I tried not to disenchant him too much. Right now, money was his pressing problem, but someday he'd like to get a B.A. and become a teacher. Teachers were the people in his life he'd most admired. I mentioned student grants and loans that he knew nothing about and persuaded him to ride the bus with me to Erindale and check it out.”

With both mentorship and friendship growing between the established writer and the budding one, we are given further glimpses into Ladoo’s early life in McBean Village. Here we discover his early education took place at a Canadian Church Mission School. Among his early reading material were what is now considered the racist and colonial works of G.A. Henty, and as Such reports (the absence of detail frustrating), “mounds of other forgotten Victoriana”. Such also gives us an insight into Ladoo’s early writing:

“As I read his vivid stories of life in McBean village, in Trinidad, some funny, some stomach-lurching, I kept looking out at the Italian Club of Erindale College playing soccer in the chill fall, rubbing their cramped calf muscles, and realised I'd been utterly reached by some of the essential human quandaries that go beyond time and place. I run a literary quarterly, Impulse, reading over a thousand submissions a year from beginning writers. Maybe a single poem scrawled while you're high in Kamloops, or volumes of delicate sensibility written by a lonely old lady in the back-woods of Ontario. I keep it up, I think, mostly because I'd like what happened that afternoon to happen again, just once. Harold was a born writer.”

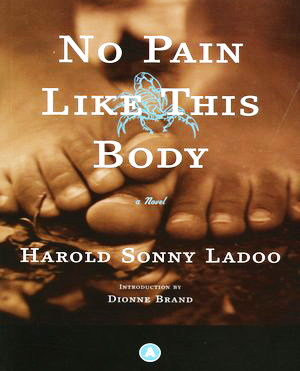

Through Such’s intervention, Ladoo attended Erindale College at the University of Toronto. It is here where Trinidadian-born Dionne Brand, Canadian poet, novelist, essayist and documentarian, would observe Ladoo smoking heavily while writing his first novel, No Pain Like This Body. Writing in 2003 in the introduction to this novel, Brand recalls: “Ladoo seemed to me, in the glimpses I had of him in the two years we attended Erindale College together at the University of Toronto, a brooding unhappy man. He smoked continually, his cheeks sucked into chasms cut out of the bony face, a permanent scowl etched there by the hard place he had come from in Trinidad, a place called McBean; mistrustful eyes made so no doubt by the same harsh landscape of subsistence agriculture he had hacked his way out of with a few others. A dismissive turn to his equally bony compact body, he occupied that farthest corner of a room in the cafeteria... Ladoo sat there in a cloud of cigarette smoke working on No Pain Like This Body.”

Brand recalls travelling along Trinidad’s roads as a girl, “through the towns of Princes Town, Rio Claro, Tableland and Mayaro…. In between and for miles on end there was nothing. Except endless fields of sugar cane relentlessly waving….” At times, Brand notes, “The eternal fields of cane were interrupted here and there by red, white and yellow jhandis – Hindu prayer flags signalling a dwelling, a devotee, a brilliant faith that had survived the arduous crossing from India. Once in a while along the empty road a woman with an orhni over her head or a girl carrying water stunned momentarily by the car would stare…”

She adds: “Secreted off this road there were traces and villages hacked out of the cane; places that African forced labour had despairingly abandoned and where Indian people had been brought two generations before as indentured labourers. An equally despairing endeavour. Their grim sense repeating and multiplying in other places called Barrackpore, Penal, Balmain, Fyzabad, Felicity, Calcutta, Palmyra, and McBean through which Ladoo observed the same desperation.”

It is out of the depths of Barrackpore, Penal, Balmain, Fyzabad, Felicity, Calcutta, Palmyra, and McBean, that Ladoo reached into to write one of the Caribbean’s most visceral, post-colonial works, No Pain Like This Body.

Sources for this exploration are: Peter Such, The Short Life and Sudden Death of Harold Sonny Ladoo (http://www.pancaribbean.com/ladoo/such.htm), and Harold Sonny Ladoo, No Pain Like This Body, House of Anansi Press Inc., 2013.