Book Review

spirit of her people

A review by Frank Birbalsingh

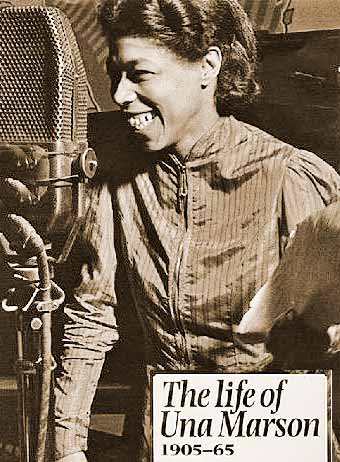

Una Marson (1905-1965) who was born in Jamaica is the author of four volumes of poems: Tropic Reveries (1930) Heights and Depths (1931) The Moth and the Star (1937) and Towards the Stars (1945) from which Dr. Alison Donnell, Reader in the Department of English Language and Literature at the University of Reading, has selected seventy-three poems for Una Marson: Selected Poems. To make up a total of eighty in the volume, two poems from Keys, the journal of the League of Coloured Peoples, are included, together with five more that were previously unpublished. The subject alone of Selected Poems justifies revival of interest in Marson - a sadly neglected figure in the history of the English-speaking West Indies.

Born the daughter of a Baptist minister, Marson won a scholarship to Hampton, the prestigious Jamaican high school in 1915. By 1928 she became Jamaica's first woman editor/publisher with her magazine The Cosmopolitan, described as "A Monthly magazine for the Business Youth of Jamaica and the Official Organ of the Stenographers Association." Marson's work on periodicals like Cosmopolitan, Keys and Public Opinion, organ of the People's National Party, founded by Norman Manley, together with speeches to "progressive" audiences confirm her activism in West Indian social and political development. She also contributed to cultural change through her poems and three plays – "At What a Price" (1931), "Pocomania" (1937), and "London Calling" (1938). Yet perhaps the only thing for which she is still remembered is her work on the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) first, in 1941, with the radio program "Calling the West Indies" and, in 1945, with the same program which she re-named "Caribbean Voices" and which aired stories and poems by authors who would later lay the foundation of modern West Indian literature – Edgar Mittelholzer, George Lamming, Samuel Selvon, V.S. Naipaul and many others.

Since Marson's activism appeared when West Indians at large were beginning to see possibility of positive political change in their condition as colonised people, her poems reflect awareness of this new possibility, and examine basic themes associated with it, for instance, racial discrimination, social justice and equal rights for women. Several poems consider the psychology of white domination through imposed stereotypes of black inferiority. The persona in "Little Boys" is a little boy who complains about racial abuse from his white school friends because he is black, and "Cinema Eyes" illustrates Hollywood type images of white superiority that breed self-hatred in black people: "But I know that black folk/Fed on movie lore/ Lose pride of race." To Marson, white domination and its corollary of black self-hatred constitute a pervasive and seemingly insurmountable problem. The persona of "Kinky Hair Blues," a young black woman who resents being forced by dominant European notions of beauty to press her hair and bleach her skin, reluctantly decides to do so purely to win a male admirer. And as its title implies, "Black Burden" laments the burden of inferiority placed on black people by a dominant white civilisation and all its works.

Meanwhile, although several poems sing the praises of Jamaica as a tropical paradise of sun, sand and sea, Marson acknowledges this as largely a tourist's view, but she does not deny the island's genuine natural gifts as in "Home Thoughts" which celebrates Jamaica's botanical richness in all its tropical splendour. "In Jamaica," however, draws attention to what their homeland realistically means for most Jamaicans: "a dreary life for the beggars," a pretty rough life in large slums, and a place where dark-skinned children are "facing a stiff fight." This sober assessment is reinforced by an old soldier who had fought in foreign wars, no doubt with the Jamaican Regiment, and has returned to Jamaica where "All it hab is poverty/ But noting more." He sums it all up: "Foreign is nice but here it hard."

Despite their social, cultural or political commentary, many of Marson's poems are devoted to a more personal issue - the pain of unrequited love. In England Marson fell in love with a younger Jamaican, who married someone else, and not until she was sixty did she get married, in the US, although, by then, she apparently suffered from depression or mental illness. Even if some of Marson's poems are touched with sentimentality her best love poems summon up enough intellectual rigour to redeem any emotional depth to which she might sink. Just as her best poems about race expose ingrained inequality without flinching or hysterics, so does the female persona in "Reasoning" stoically accept her rejection with resignation. And in "Love Songs" the persona's firm assertion: "I sing of love/ Because I am a woman" represents neither weak kneed submission to male domination nor a simple theoretical claim of gender equality, but rather a balanced, womanist point of view.

As for the stilted romantic diction in many of Marson's poems, their Wordsworthian rhythms and rhymes, or their influence by Blake's theology about white representing evil and black good, it all goes to show the author as a product of the Caribbean in the 1920s and 30s. Nor does this detract from her musical gifts or versatility, for example, in skilfully using the Shakespearean sonnet form in her poem "Winifred Holtby" and the Petrarchan form in her sonnet to the International Alliance of Women for Suffrage and Equal Citizenship. Most of all her mastery of Jamaican creole speech, reminiscent of Louise Bennett, allows her to capture the exact flavour of speech, thought and action in the religious spirit worship of a poem like "Gettin de Spirit," or in the authentic drama of a Jamaican labourer's despairing wish for divine rescue from human misery in "The Stonebreakers." In all Marson truthfully documents the authentic experience of her people who, despite distortion and disablement by colonialism, never lose faith, as we see in "There will Come a Time" a Christian vision: "Of oneness for the world's humanity."