Book Review

A review by Frank Birbalsingh

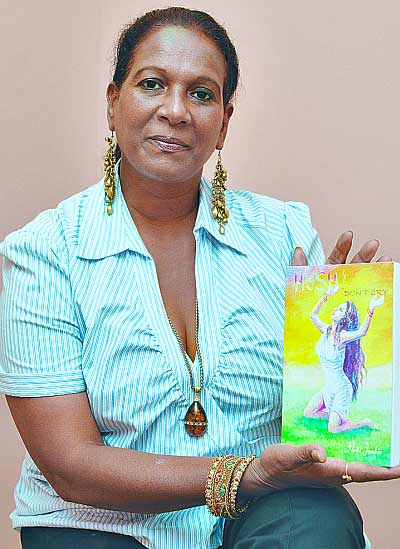

Ariti Jankie's novel Hush Don't Cry dramatises the experience of an Indo-Trinidadian woman Meera Roopnarine after she marries an Indian national - Kapil Verma. Meera belongs to a community of descendants of Indians brought as indentured workers to the Caribbean since the middle of the nineteenth century. Her story exposes her Indo-Trinidadian community's natural but sometimes superstitious interest in India as their motherland. During one visit, upon arriving in India, she: "understood her mother's devotion to the land of her ancestors, and her countrymen's thirst for anything Indian." The subject seems well suited to an author who is herself Indo-Trinidadian and has worked as a journalist in Trinidad, England and India where she studied at the Indian Institute for Mass Communications in New Delhi. Jankie also migrated to India in 1992 and, in 2005, returned to Trinidad where she now works at the Trinidad Express.

By the 1990s when the action of Meera's story begins Indians were no longer impoverished coolies: "They [Indo-Caribbeans] had conquered the degradation of poverty, to climb the rungs of the economic ladder during two oil booms and had emerged into a middle class while others were on the brink of high society." This explains why, despite being the last child in a family of ten who live in the rural Trinidadian village of Merauli, Meera is able to advertise in an Indian newspaper and find an Indian husband who, by sheer virtue of his Indianness, assumes exalted prestige as: " 'the doctor from India' in a land [Trinidad] where India was worshipped from afar." Such is their affluence that, Meera's family think nothing of the expense of air travel and having two wedding ceremonies, one in New Delhi, India, followed by a honeymoon in England where she has a brother, and another ceremony when she and her husband return home to Trinidad.

So far, ceremonial excess and ostentation indicate that all is sweetness and light for Kapil and Meera who live in her family home while he works as a doctor. Soon afterwards, her pregnancy confirms great expectations ahead for Meera and her family. Meera was: "one of the lucky girls of Indian origin on the island who had the chance to marry an Indian." But Meera also notices Kapil's aloofness, his refusal to share his earnings with her, and his apparent plan to: "live off her [Meera's] family." Worst of all, when Meera introduces her idea of opening a hair dressing salon, Kapil reacts by kicking her severely. Suddenly, great expectations decline into feelings of terror and premonitions of horror: "She [Meera] looked at him [Kapil] and saw herself buried alive." By this time too, who can blame Meera for thinking, so far as married life is concerned: "Hers was melting into a continuing nightmare!"

It adds further insult to injury for Kapil to have affairs first with a woman named Jennifer, then with another called Kathy Ann. The author now sees Kapil as: "a bomb waiting to explode," and the explosion happens when he performs an abortion on Kathy-Ann and she dies. In order to avoid possible prosecution, Kapil and his family hurriedly leave for India. They stop over in New York where they stay with another of Meera's relatives. It is when Kapil reflects on the impossibility of working in the US that we discover the truth about his prestige and professionalism as a doctor in Trinidad: his qualifications are bogus; he had spent only one year in medical school in India, and he ruefully admits: "how easy it was to have certificates copied at Indian street corners." Nevertheless Kapil's violent behaviour continues after the birth of his son – Kabir – in New York, his drunken abuse leading eventually to police intervention and deportation with his family to India.

But life with Kapil's family in his Indian home village of Lakhanpur turns out even worse for Meera who becomes a virtual slave not only to Kapil but also to his mother and sister. In one incident, because he considers her improperly dressed, Kapil grabs Meera by the hair and smashes her into a wall and, in another, because she serves an insufficiently cooked chapatti, Meera's mother-in-law clamps her hand down on the "tawa" or hotplate until she screams. Exposure of such gross intra-family female victimisation in Indian culture is another theme in Hush Don't Cry, second only to the superstitious glorification of India by Indo-Caribbeans, and it is corroborated both by: "common behaviour meted out to daughters-in-law throughout the country [India]," and by: "stories of bride burning."

No wonder Meera escapes back to Trinidad where she builds up a prosperous business as a caterer. But partly influenced by traditional injunctions of her duty as a Hindu wife, she and her children return to Lakhanpur where she helps Kapil financially to build a house. When Kapil's abuse resumes, however, Meera appeals for help to the embassy of Trinidad and Tobago in India. The title of the novel is the consoling greeting of an Afro-Trinidadian embassy official when he first observes Meera's pitifully battered condition, and decides to help her return home.

An "Epilogue" recounts events ten years later after Meera has become: "an independent, wealthy businesswoman," and her family are reunited with her in Trinidad. But Kapil's violence flares up again except that, this time, Kavita defends her mother, staying with her, while Kapil and Kabir return to India. Despite its swift, melodramatic, almost mechanical changes of mood and action, for example, Kapil's seemingly genetic predisposition to violence, Meera's miraculous powers of physical and financial self-regeneration, and Kapil's escape - scot free - from legal implications of causing Kathy-Ann's death, Jankie's exposé of female victimisation in Hush Don't Cry remains convincing because it is backed up by examples of similar victimisation in historical records of Indian indenture and in novels like The Swinging Bridge by another Indo-Trinidadian Ramabai Espinet.