Book Review

A review by Frank Birbalsingh

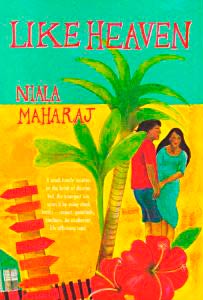

In length certainly Niala Maharaj's Like Heaven vies with V.S. Naipaul's A House for Mr. Biswas (1960) for pride of place among novels chiefly concerned with Indian-Trinidadians. Maharaj is herself an Indian-Trinidadian who studied creative writing at the University of Boston and worked as a journalist, television producer and communications consultant before settling in Amsterdam. Like Heaven is her third book, after The Queen of Coconut Chutney, a volume of short stories, and a non-fiction work - The Game of the Rose: The Third world in the Global Flower Trade.

If A House for Mr. Biswas is the saga of an Indian-Trinidadian Hindu family – the Tulsis – in the 1930s and 1940s, Like Heaven is a more rousing recitation of the fortunes of another fictional Indian-Trinidadian Hindu business family – the Sarans – during a period of about 15 years, immediately before the first ever Indian-Trinidadian-led government was elected in 1995. Following his father's heart attack, Ved Prakash Saran, the narrator, gives up plans for university study in order to carry on his parents' small, furniture business. Ved transforms the business by innovations such as sponsorship of a steelband – Saran's Symphonia – in local carnival celebrations, and the introduction of other enterprises that expand into a gigantic commercial project spread over several districts – Croissee, Dorado and Balandra – all under the banner of the "Saran empire." Such is Ved's boundless energy, ambition and creativity, and so loyal are his workers that the rise of his empire attracts suspicion from the press: "the Sarans practised some obscure form of Hindu witchcraft."

The only witchcraft is a combination of entrepreneurial daring with unremitting labour and managerial skill with employees imbued by similar enthusiasm. Ved's employees reflect the ethnic variety of groups brought to Trinidad under colonialism, for example, Suzanne his store manager who is of mixed (African and European) blood, Nerissa an Indian Muslim, and Charlo a black or African-Trinidadian master carpenter and steelband leader who, in view of the sickness of Ved's father, may be considered as Ved's surrogate father. Other workers include Bernard and Tony Antoine who are partly of Corsican ancestry as further proof of the polyglot ethnicity of Trinidadians. In addition, some of Ved's relatives – his cousin Ashok and brother Robin – also work for the Saran empire. But complications involving female family members, such as Ved's sisters and Anjani Gopaul (Anji) who becomes his wife eventually puncture the balloon of Ved's commercial success and lead to turmoil and change at the end.

Our strongest impression of this diverting narrative is its sheer vigour and vitality, and rollicking sense of outrageous fun wrapped loosely within lavishly ladled layers of wit and irony. That Ved's grand economic enterprise involving huge sums of money and an extensive network of contacts with business partners and government officials should be simply dismissed by a sleazy slur against his ethnicity catches the essential paradox, half comic half serious, at the heart of the society being described! This is conveyed directly by the author's commentary itself, and often by opinions that characters express about each other, for example, Charlo's report on Ved's irresistible feelings for his white lover Janet Stevenson: "Tiger don't phase he. Hurricane don't worry him. Getting condemned by the archbishop does roll off he back like grease off a hot frying pan. But let one white woman leave him and he does dry up and shrivel." Ved's mother - Ma – has a tongue hot like pepper, as he frankly admits: "My mother was one of the most difficult, obstreperous, demanding human beings ever created by the process of evolution, but in the midst of her unreasonable behaviour there was a kernel of irony." As Ved suggests, Ma never holds back: "What Trinidad know about civilised? Set of thief and robber running this country. All they know how to do is wine their waist at Carnival."

Nor are these quotations arbitrary or mischievous: they tie in with one cardinal notion, Naipaulian in essence: that the Caribbean, Trinidad most of all, is tragic and comic at the same time. Interestingly, Maharaj claims that she found it impossible to write about Trinidad until she read Naipaul's Miguel Street. One attraction must have been Naipaul's comic touch in treating tragic themes of loss, abandonment and corruption that impressed Maharaj. At any rate, the title of Like Heaven appears in its main epigraph, a quotation from Derek Walcott's Nobel Prize lecture which describes Port-of-Spain as: "A downtown babel of shop signs and streets, mongrelized, polyglot, a ferment without history, like heaven." Yet, another quotation from Walcott's poem "The Spoiler's Return" which serves as epigraph to Part Three of the novel makes a contradictory claim: "Hell is a city much like Port-of-Spain." Are heaven and hell the same? Although Naipaul and Walcott are nowadays at daggers drawn, so far as their art is concerned, they evidently could not agree more about the improbable, contradictory contrariness of their common Caribbean culture.

For Walcott and Naipaul, and no less than for Maharaj, ethnicity is central. Like Heaven is riddled with racial slurs by Indians against Africans and, equally, there are anti-Indian slurs like the press report mentioned above and Anji's constant sneering: "That's what matters, eh! Property and inheritance. That's all Indian culture is about." In the end, Ved admits to: "guilt and shame... with our [Saran] quarrelling and arrogance and greed." For him, the reflection of the moon in Nerissa's eyes "was like the gates to heaven." He comes to live with Nerissa, fathers her child and further admits: "Nerissa had really lived, had lived in touch with the earth, while I had merely existed in a sort of fantasy." Maharaj deserves credit for an expert plot and especially for her feat in writing in a man's voice, with equal enthusiasm and conviction, about everything including food: "dalphouri and curried chicken ... home-baked bread and cassava pone, home-baked ham, home-baked piccalilli and black fruitcake."

human stories

Refugee, justice, truth, racism, poverty and advantage are words that identify matters affecting human beings irrespective of their ethnicity or nationality. However in the minds of average citizens they do not associate these issues with individuals known or identified as authors. So when there are announcements about authors' festivals being staged, people who believe they have nothing in common with the literary types tend to stay away. Some actually believe by being in the presence of authors is a waste of time. But the opposite is true.

All the foregoing matters were on the lips of authors who participated in the 32nd International Festival of Authors at the Harbourfront Center downtown. Indeed our own Rabindranath Maharaj, winner of the 2011 Toronto Book Award for his latest novel The Amazing Absorbing Boy, observed that the people whom he writes about do not come to festivals where he presents their stories. His book which is set in Regent Park with its diverse population, also won the 2010 Trillium Book Award. Yes, he misses the Caribbean and other ethnic people who inspire his work and he is troubled by that reality. They are hardly ever there.

During the festival Maharaj hosted finalists for the Rogers Writers' Trust Fiction prize - Clark Blaise, Michael Christie, Patrick deWitt, Dan Vyleta. And Esi Edugyan.

He is very mindful that his constituents about whom he writes, unfortunately, very rarely offer him feedback. "The people that I write about I want to get more feedback from these people. They don't show up, whether it's Trinidadians, whether it is people from the Caribbean, whether it is immigrants and so on."

He wonders whether going to readings or communicating with writers is not a big part of that of their culture. While trying desperately to understand the attitude Maharaj, the former school teacher and award winning author, yearns to hear from his subjects. The latest book that has captured two major awards in a row centres around the Regent Park neighbourhood. Maybe that would bring about a change.

"I think that sometimes I kind of feel little bit slightly distressed. Maybe that is a little too strong a word," he concluded.

He would like his books to be more available here within the Caribbean community as well as in parts of the Caribbean for easy access.

There were 20 round table sessions where authors were engaged in debates on matters like "Fact versus Fiction", "On the Outside Looking In", "Magic, Myth and Forces Beyond Reason", "Home Economics" and a plethora of issues that directly impacts on the lives of our readers. But being absent from the realms of the festival you would not know that your concerns were being addressed by these creative individuals – our brothers and sisters.

Jamaica's Olive Senior engaged with Elizabeth Hay and Prue Leith during a session in which they examined "Fact versus Fiction".

The Saturday afternoon panel of authors assembled in the Lakeside Terrace, examined the impact that fact had on the fiction their craft churned out. They have had individual experiences with journalism in their respective native homelands – Jamaica, South Africa and here in Canada.

Rather frank about their early beginnings the three women despised what they had presented as writing in the early days of their respective careers. The one exception was Senior who accidentally began working as a journalist as a teenager and still a high school student. She did that for two years before accepting a scholarship to further study journalism in Canada. The well published author admitted that journalism's strict rules helps in many ways to perfect her creativity.

Nuruddin Farah, a Somalia native, author of 11 novels, which have been translated into 17 languages came to the IFOA with his latest creation "Cross Bones".

As a member of a panel discussing "From the Outside Looking In" at Africa Sunday he advocated vociferously for writers to speak the truth about his country. Farah said Somalia is a country most lied about. "People fly in and without understanding the complexity of the situation, are writing books," he observed.

He felt compelled to compare Somali with a doctor and patient relationship where if the doctor doesn't know the patient's symptoms, he or she cannot prescribe a cure. "The physician must know the ailment, the thing you're suffering from before they can prescribe the right medicine," he opined.

"In Somalia, in the rest of Africa usually many of the people who write about [the continent], including some of the Africans, have really no wherewithal, no knowledge, no understanding of the psychology and all that goes with it in that way," he argued.

Others on the panel were two Canadians - Gary Geddes and Emma Ruby-Sachs.