Book Review

A review by Frank Birbalsingh

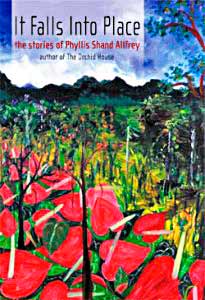

The nine stories that appear in It Falls into Place: The stories of Phyllis Shand Allfrey are a fraction of Phyllis Shand Allfrey's fictional output that includes altogether about twenty stories, a novel The Orchid House - her magnum opus - and three unpublished novels. (Allfrey also wrote poems and had a lifelong career as a journalist.) In any case, Professor Lizabeth Paravisini-Gebert's retrieval of Allfrey's stories from little known or forgotten journals and newspapers, and their exposure especially to younger West Indians is an inestimable service to our literary and cultural history.

Phyllis Shand Allfrey (1908-1986) was a white West Indian whose English family had lived in Dominica for three hundred and fifty years. Born Phyllis Byam Shand, she lived in Dominica until she was nineteen and, in 1927, met Robert Allfrey in England and got married. During the World War Two period, she was active as a Fabian socialist, associating with the British Labour Party and working, for instance, with the well known socialist author Naomi Mitchison and with the Parliamentary Committee for West Indian Affairs. In 1954, however, Allfrey returned to Dominica where she founded the Dominica Labour Party and, after winning a seat in elections of the newly formed West Indian Federation, became Minister of Labour and Social Affairs in the Federation. The sudden collapse of the Federation in 1962 then started a downward spiral in Phyllis's political career after she was forced out of the party she had founded, but she bravely launched her own newspaper The Dominica Star and maintained it until 1982, struggling against all odds, including poverty, without abandoning her socialist or libertarian ideals.

"O Stay and Hear" the first story in It Falls into Place studies relations between a white couple and their brown maids in a Caribbean setting. There is no hint of acrimony in the explicit master/servant divide when the mistress whose name itself – Madame-la – gives away the story's lightness of touch, sees her maid straightening her hair and says to her husband: "I can't think... why they [the maids] should want to have hair as straight as ours, when they mock at us so." Her irony is no more than slight or glancing, almost playful.

Similar irony again appears in "Breeze" the story of a fourteen-year-old, delinquent Dominican girl, a known ruffian and jailbird, who had: "hit a policeman, sent him to hospital for weeks, kicked the matron, jumped the prison wall and disappeared into the hills." In "Breeze" the affluent ten-year-old, white narrator is relaxing in her secluded back garden lawn when she is rudely interrupted by Breeze who literally drops out of a mango tree and threatens to bite her unless she gives up her golden bracelet which Breeze snatches before escaping. Throughout this ordeal the narrator "huddled petrified;" yet, curiously, she is also "fascinated", and thinks of Breeze "with fond partisanship." The only explanation we get of the narrator's curiously ambivalent reaction is: "perhaps ... my loyalty to her [Breeze's] enviable freedom." There is a similar reaction in Wide Sargasso Sea, the celebrated novel of Jean Rhys, another white Dominican, whose white West Indian heroine Antoinette, shows similar loyalty when she is about to die in England, and calls out to her black childhood friend Tia.

In "Parks" the scene shifts to New York where Minta Farrar, a mixed blood West Indian passes for white and is married to a white American. One night while her husband is away Minta instinctively dresses in "the costume of a native West Indian belle" and goes to the Trinidad Nightclub where she happily mingles with fellow West Indians and dances all night with a Barbadian, leaving him some money at the end. The escapade relieves her "torpor" which was "dangerous" and threatened her "like a sense of doom." Allfrey compares Minta to the heroine in Tennyson's poem "The Lady of Shalott," a lady who was doomed by a mysterious curse to look at life only through a mirror, and dies one day when she looks out of a window. Minta too is apparently cursed, but by guilt: while her status as a white West Indian assigns her to a dominant position over her fellow West Indians, it also separates her from them.

Most stories in the volume tend to dramatise incidents from the author's family experience. "Uncle Rufus" for instance, is based on the author's Uncle Ralph who violated his white caste taboo against marriage to non-whites by marrying a coloured or mixed blood woman and having "outside" children. Some stories like "A Real Person" or "A time of Loving" relate domestic incidents touched by gentle irony or even whimsy, and "A Talk of China" portrays a young woman with a passion for socialist ideology very similar to Allfrey's.

In the title story the narrator Philip is a writer researching the life of a fictional poet Chrysotome who is based on the real life Dr. Daniel Thaly, a physician and poet who was in love with one of Allfrey's "outside" cousins. Like Thaly, Chrysotome achieves fame in France although he came from the same Caribbean island in which Philip was born and which he now regards as a: "barely civilised colony." Philip's Aunt Caroline knew Chrysotome and Philip remembers her reading George Meredith's novel Diana of the Crossways in which the heroine Diana Warwick, a strong willed woman trapped in an unhappy marriage, is inspired by Caroline Norton, an early Victorian pioneer, in the fight for women's rights. It is in recalling his aunt reading Meredith's novel that Philip is told that his romantic outlook falls into place with his role as author of a poet's biography. If Allfrey was influenced by the example of women like Caroline Norton, it is no wonder her political views ran against the grain of her ruling, white, West Indian minority status.