Book Review

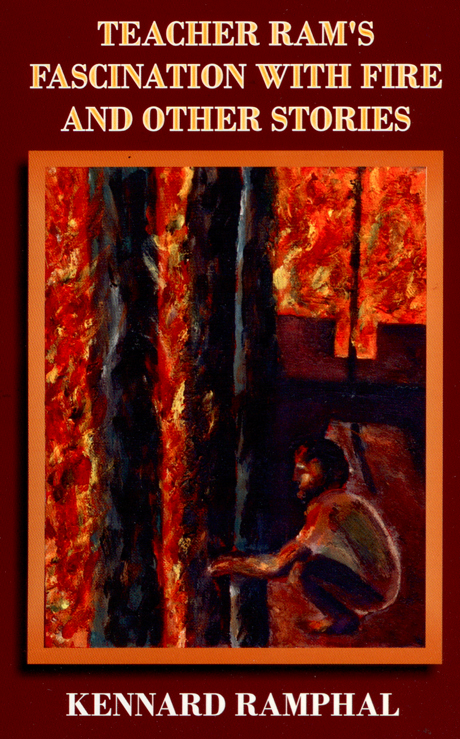

Kennard Ramphal, Teacher Ram’s Fascination with Fire and Other Stories, Toronto and North Carolina, Roraima Publishers, 2009, pp.135. ISBN: 978-0-9813751-0-6.

A review by Frank Birbalsingh

Teacher Ram’s Fascination with Fire and Other Stories is a volume of six stories by Ken Ramphal who was born in Guyana and now lives in Toronto where he teaches at the Scarborough Centre for Alternative Studies. While one story in the volume is about Guyanese immigrants in Canada, events in the other five take place in the Canal Number Two district of Guyana that recalls fiction by Guyanese authors like Peter Kempadoo (Guiana Boy), Sasenarine Persaud (Canada Geese and Apple Chatney), and most of all Rooplall Monar with his splendid fictional portraits of Guyanese plantation life in volumes such as Backdam People and Estate People.

The first story in Teacher Ram’s Fascination - “Saroo, Juror and Judge” - sets the tone of the volume by introducing a village that consists of tropical farmland reclaimed from sheer swamp through digging the second of two drainage canals – hence the name “Canal Number Two.” After working for a long time on a nearby sugar estate, Manohar Premchand - nicknamed Saroo - gives up the hard labour of sugar cane cutting when he turns 50, and settles for the less laborious life of a farmer growing vegetables such as plantains and cassava. But this quiet farming routine is broken when he is summoned to serve as a juror in the Law Court in Georgetown, the capital city of Guyana. The prospect of performing a normal civic duty lifts Saroo’s profile to such absurd heights among his fellow rustic villagers that the rest of the story is entirely devoted to his effort in meeting their ridiculous expectations.

Tension is created from the beginning by Saroo’s excessive efforts in getting his suit ironed and trousers taken to the tailor for alteration. The long journey by taxi to the stelling to catch the ferry to Georgetown, citadel of modernity and sophistication in Guyana, also builds tension, especially with much unsolicited advice from all and sundry along the way, so that by the time he sets foot in the Law Court building and is faced with the formality, routine and order of court procedure, Saroo is already in pieces, whether waiting his turn to get coffee from an urn, having his form filled in for him by a clerk because of his illiteracy, or being offered sandwiches and a soft drink for lunch. No wonder he seizes an opportunity during the lunch break to go to a market stall outside and buy a replacement meal of rice and curried fish to which he is much more accustomed. Still, when he returns to the court and his name is called out as a juror he is too flustered to recognise it, and blames his confusion on his fellow villagers: “Dem mek meh fuhget me own name.”

The climax to Saroo’s court saga comes the next day when the person on trial turns out to be Deonarine Douglas, a “dougla” or man of mixed Indian and African blood who is charged with breaking and entering with intent to steal. Whether because of his mixed race, unkempt appearance, or long hair and beard, Saroo is persuaded by Deonarine’s mere look that he is guilty. When the judge formally opens the case by asking the accused whether he pleads guilty or not, and repeats the question because of Deonarine’s hesitation, Saroo can restrain himself no longer and blurts out: “Your honour, look at that chutti wallah (professional thief’s) face. You can’t see dat the man guilty? You gon ask the man whether he guilty or not? Wha’ you expect he gon tell you? Dat he guilty?” Naturally, despite Saroo’s evident pride in his unarguable logic, the judge orders an immediate recess, Saroo’s participation is abruptly curtailed, and he is sent home.

Although his naivete is exaggerated to highlight the contrast between the rustic isolation of his fellow villagers and the urban sophistication of Georgetown’s city dwellers, Saroo is not ridiculed. It is the same in all Ramphal’s stories whether it be the deception of Kamal by Lakhan and Baloo in “A Loan Lost to Friendship” where Kamal’s loan never really gets repaid, or Farida’s alternative medical practice in “Farida and the Doctrine of Signatures” which relies more on faith or superstition rather than science: in each story human foibles and follies are exposed without being denounced. In “A Glimpse of Polly’s and Betty’s Worlds” also Polly’s simple-mindedness arouses sympathy rather than contempt, and in the title story where Teacher Ram foolishly sets fire to his farm, the quick action of neighbours ensures that the fire does not damage other farms. Similarly in the Canadian story - “Latchman’s escapade at the Bank” - although Latchman and Gobin are mistaken for bank fraudsters, no one is arrested . Ramphal’s humour is gentle, and no one suffers from the mistakes or follies either of themselves or others. Nor is anyone punished. Even rum drinking which is known as a scourge among plantation workers is portrayed as a ritual in Ramphal’s stories and regarded with something like awe precisely because of its power to subvert or sabotage. All this contrasts sharply with more biting satire in Monar’s stories, for example, which also contain poor or unsophisticated characters from rural Guyana, except that they scheme and plot and deliberately deceive or diminish each other. Whether simply comic or harshly critical, however, Ramphal’s stories employ digressive, anecdotal or episodic techniques of oral story telling that derive from folkloric traditions that are both African and Indian in origin and, in that sense, completely Guyanese.