Book Review

A review by Frank Birbalsingh

Sweetheart is the first novel of Jamaican author Alecia McKenzie who won the regional Commonwealth Writers prize for Best First book in 1992 with a collection of stories Satellite City, and followed up with two novels for young adults, and another collection Stories from the Yard. The heroine of Sweetheart is a gifted Jamaican artist, Dulcinea Gertrude Evers, who suddenly dies and is cremated before the story begins. The story consists of twelve narratives the first of which is by Dulci's closest friend Cheryl while she is en route aboard an Air Jamaica flight, taking half of Dulci's ashes from Jamaica to New York where Dulci lived and worked as a painter.

The twelve narratives drawn from Dulci's family, friends and work associates, attempt to reconstruct her biography from her schooldays in Jamaica to her spectacular success as a painter in New York, where she changed her name to Cinea Verse before her untimely death from cancer at the age of thirty-four. Since Cheryl is responsible for five narratives, we get a fascinating and many-sided portrait of Dulci from eight perspectives, and an informed meditation on Jamaican history and culture as well. McKenzie's skill in maintaining interest, coherence - and best of all, suspense - out of so many narratives goes hand in hand with technical versatility in capturing the exact features of personality and voice of each narrator whether they are old or young, male or female, American or Jamaican, friend or foe.

Carlton Beckett is a Jamaican bank manager with whom Dulci has an affair while she worked in his bank, before going to New York. Cheryl's first narrative portrays Dulci as an innocent young woman being exploited by a senior bank colleague, then physically assaulted by Carlton's wife Dakota who attacks Dulci with a cutlass in the bank, and rips off her clothes in full view of other employees, before she is rescued by a guard who fires his revolver in the air to restrain Dakota. Interestingly, in his own narrative, Carlton Beckett tells a story of Dulci being promiscuous and betraying him with a life guard during one of their love trysts in a tourist hotel. Most interesting of all is Dakota's later narrative in which she puts her finger on the central aspect of Dulci's entire life story by asking: "What was it you had, Dulcinea Evers?" For this is what provides mystery and suspense. It also explains both Dakota's former fury: "Seeing Carlton in his fever of addiction, his willingness to throw away our life together, made me go a bit mad," and her confession after attending Dulci's funeral: "As I gazed at your [Dulci's] photograph, I felt the most profound shame. I wanted to cry for both of us, for you and me." Dakota's volte face is at once poignant and persuasive, and catches the mysterious side of Dulci's elusiveness.

Other sides of Dulci come out of a narrative by Susie, an American who does not hide her dislike of Dulci although, as a professional journalist, she celebrates her artistic talent. It is a stroke of genius for the author to include an interview between Susie and Dulci in which spontaneous revelations are made, for example, when Susie observes an "insane aspect" in Dulci's paintings, and asks whether she grew up near a mental hospital. Dulci laughs out loud and replies: "The whole island [Jamaica] is a mental hospital but don't write that." Similarly, when Susie asks whether it was hard to be taken seriously as a woman artist, Dulci replies: "Nobody takes women seriously. Not even other women." The spontaneity of Dulci's almost reflex reply adds conviction to the shocking truth of sexism in the art world and beyond. All this causes Susie to refer to Dulci as an "impish child" which heightens her elusive combination of mystery, genius and daring on which the novel relies for its greatest impact. Susie sums it up as follows: "But you swam in waters that were too uncertain for me, Cinea, and I have a deep fear of drowning."

Other narratives, for example, by Dulci's father Desmond Evers, fill in details of rivalry and infighting in Dulci's family and her closeness to Cheryl, while comments by Cheryl's Aunt Mavis document, through oral history, the fundamental influence of African slavery and Maroon resistance on Jamaican culture, for instance, its legacy of African spirituality or obeah: "But people need their superstitions, don't they, Dulcinea? They need to believe in things that they can't see, and to not believe, at times, what their own eyes tell them."

Dulci's life as Cinea in New York is best described by Josh Scarbinsky, an American art teacher and critic who marries Cinea to facilitate her visa requirements for remaining in the US. Scarbinsky's comments betray a bemused mixture of professional admiration, over reaction to the exotic, and genuine love when he confesses to Cinea: "Your real talent was making people lose all sense of pride, of self, turning us into slaves." More than anyone else, it is perhaps Josh Scarbinsky who most frankly acknowledges Cinea's genius and its uncanny power in eliciting idealisation from viewers. He admits being moved by the "wild and wicked energy" of her paintings and their "bold lines and vibrating colours" which remind him of Frida Kahlo (1907-1954), Ioan Miro (1893-1983) and Amrita Shergill (1913-1941).

Kahlo was a Mexican painter whose work celebrates Mexico's indigenous traditions, Miro was a Spanish painter attracted by dualities and contradictions, and Shergill was a part-Indian, part-Hungarian artist influenced by the poverty and despair of India. If these clues do not fully explain Dulci/Cinea's elusiveness, we might turn to Cervantes' s classic novel The Adventures of Don Quixote of La Mancha in which the ageing aristocrat Don Quixote idealises Dulcinea, an ordinary peasant woman, into a figure of romance or "Sweetheart" as Dulci is often called.

peaceful world

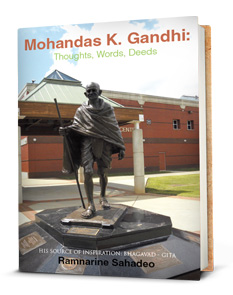

Mahatma Gandhi was a spiritual leader with no political office but exercised more power than those in positions of authority because he was a visionary with an indomitable will and a potent force dedicated to social and political reform.

"This book is put together in appreciation of one of the greatest souls of the twentieth century," Sahadeo shares.

In today's times, the author deems it appropriate to relive Gandhi's achievements in the hope that mankind can turn away from violence, anger, deceit, greed, and excessive materialism.

"If mankind is to change its current destructive direction, Gandhiji's message must remain a source of hope and inspiration if we are going to survive as a species," he adds.

Mohandas K. Gandhi: Thoughts, Words, Deeds also includes the English translation of the Bhagavad-Gita, the 700-verse Hindu scripture of Vedic philosophy that profoundly influenced Gandhi's life and actions.

For Gandhi, the Gita's stress is on attaining liberation through selfless action. Here, in his own words, is how he felt about the Holy book:

"The Gita is the universal mother. She turns away nobody. Her door is wide open to anyone who knocks. A true votary of Gita does not know what disappointment is. He ever dwells in perennial joy and peace that passeth understanding. But that peace and joy come not to skeptic or to him who is proud of his intellect or learning. It is reserved only for the humble in spirit who brings to her worship a fullness of faith and an undivided singleness of mind. There never was a man who worshipped her in that spirit and went disappointed. I find a solace in the Bhagavad-Gita that I miss even in the Sermon on the Mount. When disappointment stares me in the face and all alone I see not one ray of light, I go back to the Bhagavad-Gita. I find a verse here and a verse there, and I immediately begin to smile in the midst of overwhelming tragedies - and my life has been full of external tragedies - and if they have left no visible or indelible scar on me, I owe it all to the teaching of Bhagavad-Gita."