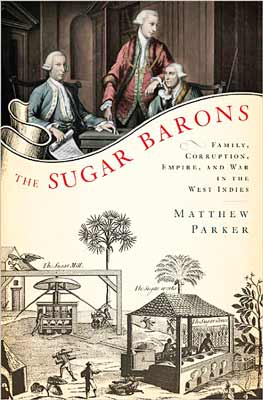

Book Review

ISBN 9780091925833

A review by Frank Birbalsingh

The Sugar Barons: Family, Corruption, Empire and War reflects on British Caribbean colonies which produced enormous wealth out of sugar plantations and the labour of African slaves, from the early seventeenth century to 1838, when slavery in all British territories was finally abolished. Matthew Parker employs references to official records as well as quotations from personal letters and documents written by sugar planters, preachers and other correspondents, to paint a richly detailed portrait of European nations scrambling, out of sheer greed, for possession of Caribbean islands three or four centuries ago. Other crops were first tried, for example, tobacco, cotton, indigo, ginger, cassava, sweet potatoes, plantains and other foodstuffs, but once sugar cane technology was mastered by the Spanish on the Canary islands, and particularly by the Portuguese on other offshore African islands like San Tome and Madeira and, after 1500, in Brazil, there was no stopping the spread of the sugar industry like wildfire across the Caribbean.

The decline of Spanish power by the end of the sixteenth century opened sluice gates for other European nations – chiefly France, England and Holland, but also Prussia, Denmark and Sweden - to join in. Parker's blunt acknowledgement of this enterprise of piracy and plunder will not reassure apologists of empire: "from the earliest days of the Spanish empire, the Caribbean was a constant theatre of violence and war, declared or not – infested by privateers, pirates, corsairs, call them what you will. It was a lawless space, a paradise for thieves, smugglers and murderers."

During the early seventeenth century, inspired by a fresh sense of anti-Catholic and anti-Spanish nationalism, English adventurers like Drake, Hawkins and Raleigh, also joined in the gory game in raw pursuit, as they saw it, of Protestantism and profit.

To begin with, Sir Thomas Warner landed settlers in St. Kitts in 1623, and a few years later another British colony was established in Barbados with white workers drawn from poorer classes of people, religious dissenters or the politically disaffected who indentured themselves in return for free passage to the colony, subsistence and wages. In 1630 the population of Barbados was 2,000, in 1636 about 10, 000 and, according to Parker, Barbados would become: "the cradle of the British West Indian sugar empire." For Barbados established a prototype for sugar monoculture in the Caribbean: by 1645, sugar accounted for forty percent of its agricultural acreage and the island no longer produced its own food. By 1700 Barbados was the wealthiest colony in the world, with more than 20,000 African slaves, and by the late eighteenth century sugar accounted for ninety-three percent of Barbadian exports. Such was the economic prestige of slavery that a slave-trading company, the Royal Adventurers into Africa, attracted investors such as King Charles the Second and the philosopher John Locke, while planters (sugar barons) like James Drax acquired enough legendary wealth from sugar to give currency to a new phrase "rich as a West Indian." Starting with only three hundred pounds in Barbados, Drax could soon afterwards buy an estate in England worth ten thousand pounds.

In "The Grandees" the second section of The Sugar Barons, Parker expatiates on the prosperity of men like Drax who returned in triumph to England where he was knighted and became influential in politics. But such ostentatious prosperity did not convey the full reality of West Indian conditions. In Jamaica, for instance, where the sugar industry began to flourish around 1676, a handful of land owners also ran the government, judiciary and military. The Governor Sir Thomas Modyford is described by a contemporary as: "the openist atheist and most profest immoral liver in the world," and the epigraph to Chapter Fifteen of The Sugar Barons quotes from a Baptist minister, James Phillipo, who describes West Indian colonies as: "one revolting scene of infamy, bloodshed and unmitigated woe, of insecure peace and open disturbance, of the abuse of power, and of the reaction of misery against oppression."

Wealth out of slavery and oppression was the dilemma behind the long drawn out controversy over the ending of the slave trade in 1807, and outright abolition of slavery itself about thirty years later. Meanwhile, decline and decadence inevitably set in through a variety of factors from soil exhaustion caused by intensive agriculture to widespread corruption of managers, merchants, money lenders, even crooked governors, frequent wars between Britain and other European nations, occasional outbreaks of disease and natural disasters, American Independence which cut valuable trading links between the Caribbean and former American colonies, competition from new sugar producers in Java and Madagascar that lowered the price of sugar, and growth of the beet sugar industry in Europe.

Cutting through all this, however, Parker correctly puts his finger on the central problem of the colonial Caribbean: "the exercise of almost unlimited authority over a turbulent community". When Christopher Codrington, Governor of Barbados, attempts to improve conditions for African slaves Parker comments: "he [Codrington] came to understand the brutal realities of the garrison society that slavery had created, where violence and fear were crucial weapons to protect the numerically inferior planters." Codrington belonged to one of the richest plantation families in Barbados, and his Christian benevolence in: "treating enslaved Africans as people rather than property" not only: "undermined the whole foundation of their society and prosperity," but contradicted: "the system on which his family had built their fortune."

Perhaps the most valuable insight in The Sugar Barons comes from its analysis of links between British Caribbean and the mainland American colonies. While the latter were regarded as places of permanent settlement, the Caribbean colonies were seen as a temporary residence suitable for absentee plantation ownership and quick riches. In Parker's view, Caribbean colonists lacked the "preserving spirit" of American colonists, not to mention: "a stable and rising population, family, long lives, religion. Instead [in Caribbean colonies] there was money, alcohol, sex and death."